Difference between revisions of "Waltharius1280"

| (5 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{| | {| | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[dixit1|Dixit]] [[et]] [[a]] [[tergo]] | + | |[[dixit1|Dixit]] [[et]] [[a]] [[tergo]] [[saltu]] [[se5|se]] [[iecit]] [[equino]], |

|1280 | |1280 | ||

|{{Commentary|Translate:'' Hoc et Guntharius fecit, nec segnior hoc fecit heros'' | |{{Commentary|Translate:'' Hoc et Guntharius fecit, nec segnior hoc fecit heros'' | ||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Pictures|[[Image:Waltharius-Lines-1285-on.png|thumb]]}} | + | |{{Pictures|[[Image:Waltharius-Lines-1285-on.png|center|thumb]]}} |

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 172: | Line 172: | ||

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}}{{Pictures|<gallery widths="180px" heights="120px" perrow="2"> | |{{PicturesCont}}{{Pictures|<gallery widths="180px" heights="120px" perrow="2"> | ||

| − | Waltharius-Lines-1285-on.png | + | File:Waltharius-Lines-1285-on.png |

File:Europe500.png | File:Europe500.png | ||

</gallery>}} | </gallery>}} | ||

| Line 193: | Line 193: | ||

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}}{{Pictures|<gallery widths="180px" heights="120px" perrow="2"> | |{{PicturesCont}}{{Pictures|<gallery widths="180px" heights="120px" perrow="2"> | ||

| − | Waltharius-Lines-1285-on.png | + | File:Waltharius-Lines-1285-on.png |

File:Europe500.png | File:Europe500.png | ||

</gallery>}} | </gallery>}} | ||

| Line 514: | Line 514: | ||

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}}{{Pictures|<gallery widths="180px" heights="120px" perrow="2"> | |{{PicturesCont}}{{Pictures|<gallery widths="180px" heights="120px" perrow="2"> | ||

| − | Waltharius-Lines-1285-on.png | + | File:Waltharius-Lines-1285-on.png |

File:Europe500.png | File:Europe500.png | ||

</gallery>}} | </gallery>}} | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment| '''ursus''' Zwierlein suggests a parallel with Aen 10,707-18. In both cases an animal that is hunted by dogs serves as a comparison for a human hero. Vergil’s boar (aper) is turned into a numid bear (numidus ursus). (Zwierlein 2004 p538-9) Yet, there is little to none literal resemblance. Parallel to a Viennese dream codex of the 10th century (Vindob. Lat. 2723, fol. 130r) “Qui ursum se infestare vidit, inimici seditionem significat.” (If one has seen an attacking bear [in a dream], a battle with an enemy is signified.) Depending on the dating of the epic, the lunar might be either a source or reception. However, Zwierlein lists earlier examples of allegorical bible exegesis, where the bear figures as the devil’s ‘bestia rapacissima’, as savage military leader or as ‘potetstas saecularis’.” In Germanic dream tradition, enemies show as wolfs, while the hero figures as a bear. (Zwierlein 2004 pp542-3) Althof, in contrast, argues that the animal dream figures are driven by a Germanic dream tradition. Dreams in Vergil and other classic authors usually dream of human beings. Althof lists multiple examples of Germanic animal dreams (Althof 1905 vol2 pp190-1) Zwierlein lists counterexamples of animal allegories in classic sources, but is not able to create a direct link to the poem (Zwierlein 2004 p540) '''Numidus ... ursus''' 'ursos ... Numidas' appear in Juvenal 4.99-100. Geographic attributes such as African lions or Armenian tigers became popular for pure poetic purposes since the neoteric period. (Zwierlein 543, FN 119) Zwierlein claims that the Waltharius takes the ‘ursus numidus’ from a wide-spread medieval schoolbook Solin’s [[Collectanea rerum memorabilium]]. (Zwierlein 2004 p543) BK}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Et]] [[canibus1|canibus]] [[circumdatus]] [[astat]] [[et]] [[artubus]] [[horret]] | |[[Et]] [[canibus1|canibus]] [[circumdatus]] [[astat]] [[et]] [[artubus]] [[horret]] | ||

| Line 545: | Line 545: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{PicturesCont}}{{Pictures|<gallery widths="180px" heights="120px" perrow="2"> | |{{PicturesCont}}{{Pictures|<gallery widths="180px" heights="120px" perrow="2"> | ||

| − | Waltharius-Lines-1285-on.png | + | File:Waltharius-Lines-1285-on.png |

File:Europe500.png | File:Europe500.png | ||

</gallery>}} | </gallery>}} | ||

| Line 558: | Line 558: | ||

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}}{{Pictures|<gallery widths="180px" heights="120px" perrow="2"> | |{{PicturesCont}}{{Pictures|<gallery widths="180px" heights="120px" perrow="2"> | ||

| − | Waltharius-Lines-1285-on.png | + | File:Waltharius-Lines-1285-on.png |

File:Europe500.png | File:Europe500.png | ||

</gallery>}} | </gallery>}} | ||

| Line 604: | Line 604: | ||

|[[Waltharius1237|« previous]] | |[[Waltharius1237|« previous]] | ||

|{{Outline| | |{{Outline| | ||

| − | * Prologue | + | * [[WalthariusPrologue|Prologue]] |

| − | * Introduction: the Huns (1–12) | + | * [[Waltharius1|Introduction: the Huns (1–12)]] |

* The Huns (13–418) | * The Huns (13–418) | ||

| − | ** The Franks under Gibich surrender to Attila, giving Hagen as a hostage (13–33) | + | ** [[Waltharius13|The Franks under Gibich surrender to Attila, giving Hagen as a hostage (13–33)]] |

| − | ** The Burgundians under Hereric surrender to Attila, giving Hildegund as a hostage (34–74) | + | ** [[Waltharius34|The Burgundians under Hereric surrender to Attila, giving Hildegund as a hostage (34–74)]] |

| − | ** The Aquitainians under Alphere surrender to Attila, giving Walther as a hostage (75–92) | + | ** [[Waltharius75|The Aquitainians under Alphere surrender to Attila, giving Walther as a hostage (75–92)]] |

| − | ** Experience of the hostages at Attila’s court (93–115) | + | ** [[Waltharius93|Experience of the hostages at Attila’s court (93–115)]] |

| − | ** Death of Gibich, flight of Hagen (116–122) | + | ** [[Waltharius116|Death of Gibich, flight of Hagen (116–122)]] |

| − | ** Attila’s queen Ospirin advises her husband to ensure Walther’s loyalty by arranging a marriage (123–141) | + | ** [[Waltharius123|Attila’s queen Ospirin advises her husband to ensure Walther’s loyalty by arranging a marriage (123–141)]] |

| − | ** Walther rejects Attila’s offer of a bride (142–169) | + | ** [[Waltharius142|Walther rejects Attila’s offer of a bride (142–169)]] |

| − | ** Walther leads the army of the Huns to victory in battle (170–214) | + | ** [[Waltharius170|Walther leads the army of the Huns to victory in battle (170–214)]] |

** The Escape (215–418) | ** The Escape (215–418) | ||

| − | *** Walther returns from battle and encounters Hildegund (215–255) | + | *** [[Waltharius215|Walther returns from battle and encounters Hildegund (215–255)]] |

| − | *** Walther reveals to Hildegund his plans for escaping with Attila’s treasure (256–286) | + | *** [[Waltharius256|Walther reveals to Hildegund his plans for escaping with Attila’s treasure (256–286)]] |

| − | *** Walther hosts a luxurious banquet for Attila’s court; eventually all his intoxicated guests fall asleep (287–323) | + | *** [[Waltharius287|Walther hosts a luxurious banquet for Attila’s court; eventually all his intoxicated guests fall asleep (287–323)]] |

| − | *** Flight of Walther and Hildegund from Attila’s court (324–357) | + | *** [[Waltharius324|Flight of Walther and Hildegund from Attila’s court (324–357)]] |

| − | *** The following day, the escape of Walther and Hildegund is discovered by Ospirin (358–379) | + | *** [[Waltharius358|The following day, the escape of Walther and Hildegund is discovered by Ospirin (358–379)]] |

| − | *** Attila is infuriated and vows revenge on Walther, but can find no one willing to dare to pursue him, even for a large reward (380–418) | + | *** [[Waltharius380|Attila is infuriated and vows revenge on Walther, but can find no one willing to dare to pursue him, even for a large reward (380–418)]] |

* The Single Combats (419–1061) | * The Single Combats (419–1061) | ||

** Diplomacy (419–639) | ** Diplomacy (419–639) | ||

| − | *** Flight of Walther and Hildegund to the area of Worms (419–435) | + | *** [[Waltharius419|Flight of Walther and Hildegund to the area of Worms (419–435)]] |

| − | *** Gunther, King of the Franks, learns of Walther’s presence on his territory and, despite Hagen’s warnings, decides to pursue him for his treasure (436–488) | + | *** [[Waltharius436|Gunther, King of the Franks, learns of Walther’s presence on his territory and, despite Hagen’s warnings, decides to pursue him for his treasure (436–488)]] |

| − | *** Walther makes his camp in a mountainous area and goes to sleep (489–512) | + | *** [[Waltharius489|Walther makes his camp in a mountainous area and goes to sleep (489–512)]] |

| − | *** Gunther and his companions approach Walther’s camp; Hagen unsuccessfully tries to dissuade the king from attacking it (513–531) | + | *** [[Waltharius513|Gunther and his companions approach Walther’s camp; Hagen unsuccessfully tries to dissuade the king from attacking it (513–531)]] |

| − | *** Hildegund sees the Franks approaching and wakes Walther, who calms her fears and prepares for battle; he recognizes Hagen from a distance (532–571) | + | *** [[Waltharius532|Hildegund sees the Franks approaching and wakes Walther, who calms her fears and prepares for battle; he recognizes Hagen from a distance (532–571)]] |

| − | *** Hagen persuades Gunther to try diplomacy before using force (571–580) | + | *** [[Waltharius571|Hagen persuades Gunther to try diplomacy before using force (571–580)]] |

| − | *** Camalo is sent as a messenger to Walther, who offers to make Gunther a gift in return for allowing his passage (581–616) | + | *** [[Waltharius581|Camalo is sent as a messenger to Walther, who offers to make Gunther a gift in return for allowing his passage (581–616)]] |

| − | *** Hagen counsels Gunther to accept the offer, but Gunther rejects this advice, calling him a coward. Insulted, Hagen goes off to a nearby hill (617–639) | + | *** [[Waltharius617|Hagen counsels Gunther to accept the offer, but Gunther rejects this advice, calling him a coward. Insulted, Hagen goes off to a nearby hill (617–639)]] |

** Combat (640–1061) | ** Combat (640–1061) | ||

| − | *** 1st single combat: Camalo is sent back to Walther, who slays him (640–685) | + | *** [[Waltharius640|1st single combat: Camalo is sent back to Walther, who slays him (640–685)]] |

| − | *** 2nd single combat: Walther slays Kimo/Scaramund, Camalo’s nephew (686–719) | + | *** [[Waltharius686|2nd single combat: Walther slays Kimo/Scaramund, Camalo’s nephew (686–719)]] |

| − | *** Gunther encourages his men (720–724) | + | *** [[Waltharius720|Gunther encourages his men (720–724)]] |

| − | *** 3rd single combat: Walther slays Werinhard, a descendant of the Trojan Pandarus (725–753) | + | *** [[Waltharius725|3rd single combat: Walther slays Werinhard, a descendant of the Trojan Pandarus (725–753)]] |

| − | *** 4th single combat: Walther slays the Saxon Ekivrid, after an exchange of insults (754–780) | + | *** [[Waltharius754|4th single combat: Walther slays the Saxon Ekivrid, after an exchange of insults (754–780)]] |

| − | *** 5th single combat: Walther slays Hadawart, after an exchange of insults (781–845) | + | *** [[Waltharius781|5th single combat: Walther slays Hadawart, after an exchange of insults (781–845)]] |

| − | *** Hagen sees his nephew Patavrid going off to fight Walther and laments the evil wreaked on mankind by greed (846–877) | + | *** [[Waltharius846|Hagen sees his nephew Patavrid going off to fight Walther and laments the evil wreaked on mankind by greed (846–877)]] |

| − | *** 6th single combat: after trying to dissuade him from fighting, Walther slays Patavrid (878–913) | + | *** [[Waltharius878|6th single combat: after trying to dissuade him from fighting, Walther slays Patavrid (878–913)]] |

| − | *** 7th single combat: Walther slays Gerwitus (914–940) | + | *** [[Waltharius914|7th single combat: Walther slays Gerwitus (914–940)]] |

| − | *** Gunther again encourages his men, giving Walther some time to rest (941–961) | + | *** [[Waltharius941|Gunther again encourages his men, giving Walther some time to rest (941–961)]] |

| − | *** 8th single combat: Walther is shorn of his hair by Randolf, whom he then slays (962–981) | + | *** [[Waltharius962|8th single combat: Walther is shorn of his hair by Randolf, whom he then slays (962–981)]] |

| − | *** Walther is attacked by Eleuthir/Helmnot, assisted by Trogus, Tanastus, and Gunther; he slays all but Gunther (981–1061) | + | *** [[Waltharius981|Walther is attacked by Eleuthir/Helmnot, assisted by Trogus, Tanastus, and Gunther; he slays all but Gunther (981–1061)]] |

* The Final Combat (1062–1452) | * The Final Combat (1062–1452) | ||

| − | ** Gunther tries to persuade Hagen to help him to defeat Waltharius; remembering his wounded honor, Hagen refuses (1062–1088) | + | ** [[Waltharius1062|Gunther tries to persuade Hagen to help him to defeat Waltharius; remembering his wounded honor, Hagen refuses (1062–1088)]] |

| − | ** Hagen changes his mind and agrees to help Gunther, but advises that they must lie low wait until Walther comes down from the mountains into open ground (1089–1129) | + | ** [[Waltharius1089|Hagen changes his mind and agrees to help Gunther, but advises that they must lie low wait until Walther comes down from the mountains into open ground (1089–1129)]] |

| − | ** Walther decides to spend the night in the mountains. He rematches the severed heads with the bodies of his victims, prays for their souls, then sleeps (1130–1187) | + | ** [[Waltharius1130|Walther decides to spend the night in the mountains. He rematches the severed heads with the bodies of his victims, prays for their souls, then sleeps (1130–1187)]] |

| − | ** The following day, Walther and Hildegund set out from the mountains, taking the horses and arms of the defeated warriors (1188–1207) | + | ** [[Waltharius1188|The following day, Walther and Hildegund set out from the mountains, taking the horses and arms of the defeated warriors (1188–1207)]] |

| − | ** Hildegund perceives Gunther and Hagen approaching to attack; the king addresses Walther (1208–1236) | + | ** [[Waltharius1208|Hildegund perceives Gunther and Hagen approaching to attack; the king addresses Walther (1208–1236)]] |

| − | ** Walther ignores Gunther and pleads with Hagen to remember the bond of their childhood friendship; Hagen counters that Walther has already broken their faith by slaying Patavrid (1237–1279) | + | ** [[Waltharius1237|Walther ignores Gunther and pleads with Hagen to remember the bond of their childhood friendship; Hagen counters that Walther has already broken their faith by slaying Patavrid (1237–1279)]] |

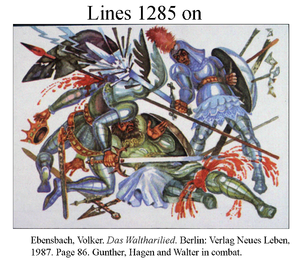

** '''The fight begins and continues for seven hours; Gunther foolishly tries to retrieve a thrown spear from the ground near Walther and is only saved from death by Hagen’s brave intervention (1280–1345)''' | ** '''The fight begins and continues for seven hours; Gunther foolishly tries to retrieve a thrown spear from the ground near Walther and is only saved from death by Hagen’s brave intervention (1280–1345)''' | ||

| − | ** Walther challenges Hagen; he severs Gunther’s leg, but Hagen again saves the king’s life (1346–1375) | + | ** [[Waltharius1346|Walther challenges Hagen; he severs Gunther’s leg, but Hagen again saves the king’s life (1346–1375)]] |

| − | ** Hagen cuts off Walther’s right hand; Walther gouges out one of Hagen’s eyes and, cutting open his cheek, knocks out four teeth (1376–1395) | + | ** [[Waltharius1376|Hagen cuts off Walther’s right hand; Walther gouges out one of Hagen’s eyes and, cutting open his cheek, knocks out four teeth (1376–1395)]] |

| − | ** Having wounded each other, the warriors end the battle, drink together, and engage in a friendly exchange of humorous taunt (1396–1442) | + | ** [[Waltharius1396|Having wounded each other, the warriors end the battle, drink together, and engage in a friendly exchange of humorous taunt (1396–1442)]] |

| − | ** The warriors return to their respective homes; Walther marries Hildegund and eventually becomes king of the Aquitainians (1443–1452) | + | ** [[Waltharius1443|The warriors return to their respective homes; Walther marries Hildegund and eventually becomes king of the Aquitainians (1443–1452)]] |

| − | * Epilogue (1453–1456)}} | + | * [[Waltharius1453|Epilogue (1453–1456)]]}} |

| | | | ||

|[[Waltharius1346|next »]] | |[[Waltharius1346|next »]] | ||

Latest revision as of 07:19, 12 December 2009

The fight begins and continues for seven hours; Gunther foolishly tries to retrieve a thrown spear from the ground near Walther and is only saved from death by Hagen’s brave intervention (1280–1345)

| Dixit et a tergo saltu se iecit equino, | 1280 | Translate: Hoc et Guntharius fecit, nec segnior hoc fecit heros

|

DSSSDS | |||

| Hoc et Guntharius nec segnior egerat heros | SDSDDS | |||||

| Waltharius, cuncti pedites bellare parati. | DSDSDS | |||||

| Stabat quisque ac venturo se providus ictu | Aeneid 3.458: venturaque bella. . . ‘The wars to come. . .’

|

SSSSDS Elision: quisque ac |

||||

| Praestruxit: trepidant sub peltis Martia membra. | Aeneid 7.182: martiaque. . .vulnera. . . ‘Wounds of war. . .’

|

SDSSDS | ||||

| Hora secunda fuit, qua tres hi congrediuntur, | 1285 | DDSSDS | ||||

| Adversus solum conspirant arma duorum. | SSSSDS | |||||

| Primus maligeram collectis viribus hastam | Maligeram: a very disputed hapax legomenon. Since the first a here is long, it should be equivalent to maliferam, (“apple-bearing,” an adjective found in Virgil) serving to figuratively describe the wood from which the hastam is made; the manuscript variant maligenam would make this easier. Perhaps more likely is that the poet, disregarding vowel-length, coined the word to mean “bearing evil.”

|

Aeneid 9.52-53: iaculum attorquens emittit in auras,/ principium pugnae. ‘Whirling a javelin, he sends it skyward to start the battle.’ Georgics 3.235: ubi collectum robur viresque refectae. . . ‘When his power is mustered and his strength renewed. . .’

|

SDSSDS | |||

| Direxit Hagano disrupta pace. sed illam | Aeneid 10.401: validam derexerat hastam. ‘He had launched his strong spear.’

|

SDSSDS | ||||

| Turbine terribilem tanto et stridore volantem | Aeineid 12.267: sonitum dat stridula cornus. ‘The whistling cornel shaft sings.’ 11.863-864.: teli stridorem aurasque sonantis/ audiit. ‘He heard the whistling dart and whirring air.’

|

DDSSDS Elision: tanto et |

||||

| Alpharides semet cernens tolerare nequire | 1290 | DSSDDS | ||||

| Sollers obliqui delusit tegmine scuti: | SSSSDS | |||||

| Nam veniens clipeo sic est ceu marmore levi | Eclogue 7.31: levi de marmore. . . ‘From polished marble. . .’ Aeneid 10.776-777.: stridentemque eminus hastam/ iecit. At illa volans clipeo est excussa proculque/ egregium Antoren latus inter et ilia figit. ‘He threw from far his whistling spear; as it flew, it glanced from the shield, and pierces noble Antores nearby between side and flank.’ 9.746: portaeque infigitur hasta. ‘The spear lodges in the gate.’

|

DDSSDS | ||||

| Excussa et collem vehementer sauciat usque | Eclogue 7.31: levi de marmore. . . ‘From polished marble. . .’ Aeneid 10.776-777.: stridentemque eminus hastam/ iecit. At illa volans clipeo est excussa proculque/ egregium Antoren latus inter et ilia figit. ‘He threw from far his whistling spear; as it flew, it glanced from the shield, and pierces noble Antores nearby between side and flank.’ 9.746: portaeque infigitur hasta. ‘The spear lodges in the gate.’

|

SSDSDS Elision: excussa et |

||||

| Ad clavos infixa solo. tunc pectore magno, | Ad clavos: up to the nails that attached the metal point to the wooden shaft.

|

Aeineid 2.544-545.: senior telumque imbelle sine ictu/ coniecit, rauco quod protinus aere repulsum/ et summo clipei nequiquam umbone pependit. ‘The old man hurled his weak and harmless spear, which straight recoiled from the clanging brass and hung idly from the top of the shield’s boss.’ Statius, Thebaid 9.533: pectore magno. . . ‘The mighty breast. . .’ Aeineid 4.448: magno. . .pectore.

|

SSDSDS | |||

| Sed modica vi fraxineum hastile superbus | 1295 | Aeineid 2.544-545.: senior telumque imbelle sine ictu/ coniecit, rauco quod protinus aere repulsum/ et summo clipei nequiquam umbone pependit. ‘The old man hurled his weak and harmless spear, which straight recoiled from the clanging brass and hung idly from the top of the shield’s boss.’ Statius, Thebaid 9.533: pectore magno. . . ‘The mighty breast. . .’ Aeineid 4.448: magno. . .pectore.

|

DSDSDS Hiatus: fraxineum hastile |

|||

| Iecit Guntharius, volitans quod adhaesit in ima | SDDDDS | |||||

| Waltharii parma, quam mox dum concutit ipse, | DSSSDS | |||||

| Excidit ignavum de ligni vulnere ferrum. | DSSSDS | |||||

| Omine quo maesti confuso pectore Franci | Aeineid 7.146-147.: omine magno/ crateras laeti statuunt. ‘Cheered by the mighty omen, they set on the bowls.’

|

|

DSSSDS | |||

| Mox stringunt acies, dolor est conversus ad iras, | 1300 | Aeineid 2.594: quis indomitas tantus dolor excitat iras? ‘What resentment thus stirs ungovernable wrath?’

|

SDDSDS | |||

| Et tecti clipeis Aquitanum invadere certant. | Aeneid 2.227: clipeique sub orbe teguntur. ‘They nestle under the circle of her shield.’

|

|

SDDSDS Elision: Aquitanum invadere |

|||

| Strennuus ille tamen vi cuspidis expulit illos | DDSDDS | |||||

| Atque incursantes vultu terrebat et armis. | Prudentius, Psychomachia 196: vultuque et voce minatur. ‘She menaces with look and speech.’

|

SSSSDS Elision: atque incursantes |

||||

| Hic rex Guntharius coeptum meditatur ineptum, | SDSDDS | |||||

| Scilicet ut iactam frustra terraeque relapsam, | 1305 | Iactam…relapsam: with hastam, line 1307.

|

DSSSDS | |||

| Ante pedes herois enim divulsa iacebat --, | DSDSDS | |||||

| Accedens tacite furtim sustolleret hastam, | Aeneid 9.546-547.: furtim/ sustulerat. ‘She had borne [him] secretly.’

|

SDSSDS | ||||

| Quandoquidem brevibus gladiorum denique telis | Brevibus gladiorum…telis: “the short reaches of their swords”

|

DDDSDS | ||||

| Armati nequeunt accedere comminus illi, | SDSDDS | |||||

| Qui tam porrectum torquebat cuspidis ictum. | 1310 | Cuspidis ictum equiv. to telum

|

Aeneid 7.756: cuspidis ictum. . . ‘The stroke of the spearpoint. . .’

|

SSSSDS | ||

| Innuit ergo oculis vassum praecedere suadens, | Vassum: “vassal,” i.e., Hagen. A word of Celtic derivation.

|

DDSSDS Elision: ergo oculis |

||||

| Cuius defensu causam supplere valeret. | Causam supplere valeret equiv. to [rex] rem perficere posset

|

SSSSDS | ||||

| Nec mora, progreditur Haganon ac provocat hostem, | DDDSDS | |||||

| Rex quoque gemmatum vaginae condidit ensem, | Prudentius, Psychomachia 105: condere vaginae gladium. ‘To sheathe the sword. . .’ Ovid, Metamorphoses 13.392: letalem condidit ensem. ‘He plunged his fatal sword.’

|

DSSSDS | ||||

| Expediens dextram furto actutum faciendo. | 1315 | Aeineid 12.258: expediuntque manus. ‘They spread out their hands.’

|

DSSSDS Elision: furto actutum |

|||

| Sed quid plura? manum pronus transmisit in hastam | SDSSDS | |||||

| Et iam comprensam sensim subtraxerat illam | Sensim subtraxerat: here the adverb clearly shows that the pluperfect has been substituted for the imperfect metri causa.

|

SSSSDS | ||||

| Fortunae maiora petens. sed maximus heros, | Fortunae equiv. to a fortuna

|

SSDSDS | ||||

| Utpote qui bello semper sat providus esset | DSSSDS | |||||

| Aeter et unius punctum cautissimus horae, | 1320 | Praeter…unius punctum…horae: “except for one moment of time,” a foreshadowing of lines 1381 ff.

|

DSSSDS | |||

| Hunc inclinari cernens persenserat actum | SSSSDS | |||||

| Nec tulit, obstantem sed mox Haganona revellens, | Revellens equiv. to pellens

|

Aeineid 8.256: non tulit Alcides. ‘Alcides did not tolerate this.’

|

DSSDDS | |||

| Denique sublato qui divertebat ab ictu, | Divertebat: Hagen “was stepping back from.”

|

DSSSDS | ||||

| Insilit et planta direptum hastile retentat | DSSSDS Elision: direptum hastile |

|||||

| Ac regem furto captum sic increpitavit, | 1325 | : Aeineid 10.810: Lausum increpitat. ‘He chides Lausus.’ 5.431-432.: tarda trementi/ genua labant. ‘His slow knees totter and tremble.’ 12.905: genua labant, gelidus concrevit frigore sanguis. ‘His knees buckle, his blood is frozen cold.’

|

SSSSDS | |||

| Ut iam perculso sub cuspide genva labarent. | Perculso sub cuspide equiv. to [regi] perculso quasi a cuspidis ictu. (Much debated. Cuspis is a femine noun, but cf. line 857.) Genva equiv. to genua (synizesis)

|

: Aeineid 10.810: Lausum increpitat. ‘He chides Lausus.’ 5.431-432.: tarda trementi/ genua labant. ‘His slow knees totter and tremble.’ 12.905: genua labant, gelidus concrevit frigore sanguis. ‘His knees buckle, his blood is frozen cold.’

|

SSSDDS | |||

| Quem quoque continuo esurienti porgeret Orco, | Porgeret equiv. to porrexisset

|

Aeineid 9.785: iuvenum primos tot miserit Orco? ‘Shall he send down to death so many of our noblest youths?’ 2.398: multos Danaum demittimus Orco. ‘Many a Greek we sent down to Orcus.’ Prudentius, Psychomachia 501-502.: et fors innocuo tinxisset sanguine ferrum,/ ni Ratio armipotens. . .clipeum obiectasset et atrae/ hostis ab incursu claros texisset alumpnos. ‘And perchance she would have dippedher steel in their innocent blood, had not the mighty warrior Reason put her shield in the way and covered her famed foster-children from their deadly foe’s onslaught.’

|

DDDSDS Elision: continuo esurienti |

|||

| Ni Hagano armipotens citius succurreret atque | Aeineid 9.785: iuvenum primos tot miserit Orco? ‘Shall he send down to death so many of our noblest youths?’ 2.398: multos Danaum demittimus Orco. ‘Many a Greek we sent down to Orcus.’ Prudentius, Psychomachia 501-502.: et fors innocuo tinxisset sanguine ferrum,/ ni Ratio armipotens. . .clipeum obiectasset et atrae/ hostis ab incursu claros texisset alumpnos. ‘And perchance she would have dippedher steel in their innocent blood, had not the mighty warrior Reason put her shield in the way and covered her famed foster-children from their deadly foe’s onslaught.’

|

DDDSDS Elision: Hagano armipotens Hiatus: ni Hagano |

||||

| Obiecto dominum scuto muniret et hosti | Aeineid 12.377: clipeo obiecto conversus in hostem/ ibat et auxilium ducto mucrone petebat. ‘He, with his shield before him, turned and was making for his foe, seeking aid from his drawn sword.’

|

SDSSDS | ||||

| Nudam aciem saevi mucronis in ora tulisset. | 1330 | DSSDDS Elision: nudam aciem |

||||

| Sic, dum Waltharius vulnus cavet, ille resurgit | Ille: Gunther

|

SDSDDS | ||||

| Atque tremens studiusque stetit, vix morte reversus. | Actus Apostolorum 9.6: tremens ac stupens dixit. . . ‘He, trembling and astonished, said. . .’ Statius, Silvae 5.1.172: media de morte reversa/ mens. . . ‘Her mind returning from the midst of death. . .

|

DDDSDS False quantities: STUPIDUSQUE? |

||||

| Nec mora nec requies: bellum instauratur amarum, | Aeneid 5.458; 12.553; Georgics 3.110: nec mora nec requies. ‘No rest, no stay is there.’ Aeineid 2.669-670.: sinite instaurata revisam/ proelia. ‘Let me seek again and renew the fights.’

|

DDSSDS Elision: bellum instauratur |

||||

| Incurrunt hominem nunc ambo nuncque vicissim; | SDSSDS | |||||

| Et dum progresso se impenderet acrius uni, | 1335 | Se impenderet: Waltharius

|

SSSDDS Elision: se impenderet |

|||

| En de parte alia subit alter et impedit ictum. | Aeineid 5.339: post Helymus subit. ‘Behind comes Helymus.’ 10.877: subit obvius. ‘He moves forward to meet him.’

|

SDDDDS Elision: parte alia |

||||

| Haud aliter, Numidus quam dum venabitur ursus | Venabitur: present passive sense

|

Aeineid 10.714: haud aliter. . . ‘Just so. . .’

|

|

DDSSDS | ursus Zwierlein suggests a parallel with Aen 10,707-18. In both cases an animal that is hunted by dogs serves as a comparison for a human hero. Vergil’s boar (aper) is turned into a numid bear (numidus ursus). (Zwierlein 2004 p538-9) Yet, there is little to none literal resemblance. Parallel to a Viennese dream codex of the 10th century (Vindob. Lat. 2723, fol. 130r) “Qui ursum se infestare vidit, inimici seditionem significat.” (If one has seen an attacking bear [in a dream], a battle with an enemy is signified.) Depending on the dating of the epic, the lunar might be either a source or reception. However, Zwierlein lists earlier examples of allegorical bible exegesis, where the bear figures as the devil’s ‘bestia rapacissima’, as savage military leader or as ‘potetstas saecularis’.” In Germanic dream tradition, enemies show as wolfs, while the hero figures as a bear. (Zwierlein 2004 pp542-3) Althof, in contrast, argues that the animal dream figures are driven by a Germanic dream tradition. Dreams in Vergil and other classic authors usually dream of human beings. Althof lists multiple examples of Germanic animal dreams (Althof 1905 vol2 pp190-1) Zwierlein lists counterexamples of animal allegories in classic sources, but is not able to create a direct link to the poem (Zwierlein 2004 p540) Numidus ... ursus 'ursos ... Numidas' appear in Juvenal 4.99-100. Geographic attributes such as African lions or Armenian tigers became popular for pure poetic purposes since the neoteric period. (Zwierlein 543, FN 119) Zwierlein claims that the Waltharius takes the ‘ursus numidus’ from a wide-spread medieval schoolbook Solin’s Collectanea rerum memorabilium. (Zwierlein 2004 p543) BK | |

| Et canibus circumdatus astat et artubus horret | Artubus: “paws”

|

Aeineid 10.714: haud aliter. . . ‘Just so. . .’

|

DSDDDS | |||

| Et caput occultans submurmurat ac propiantes | Caput occultans: “with head low” Propiantes equiv. to appropinquantes

|

DSSDDS | ||||

| Amplexans Umbros miserum mutire coartat, | 1340 | Amplexans: ironic sense Umbros: hunting hounds from Umbria in Italy Miserum: adverbial

|

|

SSDSDS | ||

| Tum rabidi circumlatrant hinc inde Molossi | Molossi: hunting hounds from Epirus

|

Aeineid 7.588: multis circum latrantibus undis. . . ‘Amid many howling waves. . .’

|

|

DSSSDS | ||

| Comminus ac dirae metuunt accedere belvae --, | Aeineid 10.712: nec cuiquam irasci propiusque accedere virtus. ‘No one is brave enough to rage or come near it.’

|

DSDSDS | ||||

| Taliter in nonam conflictus fluxerat horam, | DSSSDS | |||||

| Et triplex cunctis inerat maceratio: leti | Maceratio equiv. to tormentum, supplicium

|

SSDDDS | ||||

| Terror, et ipse labor bellandi, solis et ardor. | 1345 | DDSSDS |