Waltharius489

Revision as of 21:51, 12 December 2009 by Michelle De Groot (talk | contribs) (→Walther makes his camp in a mountainous area and goes to sleep (489–512))

Walther makes his camp in a mountainous area and goes to sleep (489–512)

| Interea vir magnanimus de flumine pergens | Vir magnanimus: Waltharius

|

DSDSDS | "magnanimus": literally, great-souled, great-hearted. The word implies generosity but also an heroic greatness of spirit beyond mere kindness. Dante frequently uses an Italian cognate of the word to describe figures who, while damned, retain inherent nobility, such as Virgil or Farinata degli Uberti. MCD | |||

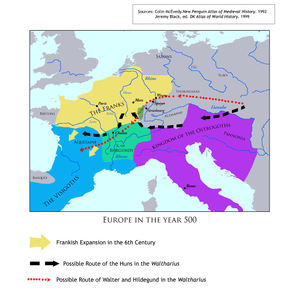

| Venerat in saltum iam tum Vosagum vocitatum. | 490 | Vosagum: the name properly belongs not just to a saltus but to the region of the Vosges Mountains, now in north-eastern France.

|

DSSDDS | The area around Worms falls outside of the defined modern boundaries of the Vosges. Walther and Hildgund had most likely reached only the northernmost peaks of the Vosges, made of sandstone and rising to (comparatively) low heights around 2000 feet. Further south, the Vosges become granite and rise much higher. Throughout, however, they would have been covered by thick forest, resembling the Black Forest in age and density. MCD | ||

| Nam nemus est ingens, spatiosum, lustra ferarum | Georgics 2.471: illic saltus ac lustra ferarum. ‘They have woodland glades and haunts of game.’ Aeineid 3.646-647.: vitam in silvis inter deserta ferarum/ lustra domosque traho. ‘I began to drag out my life in the woods among the lonely lairs and haunts of wild beasts.’ 3.432: canibus resonantia saxa. . . ‘Rocks that echo with her hounds. . .’

|

DSDSDS | The Waltharius-poet creates an odd variant of the classical locus amoenus, in which a beautiful place is described. Indeed, the use of the word "nemus," often associated with sacred groves, would lead us to expect a peaceful or beautiful place. However, this nemus is "ingens," and home to wild beasts. As a place of apparent but deceptive refuge, it has more in common with Virgil's island of the Cyclops, which also is home to "lustra ferarum." MCD | |||

| Plurima habens, suetum canibus resonare tubisque. | Suetum canibus resonare tubisque: i.e., a popular place for hunting.

|

Georgics 2.471: illic saltus ac lustra ferarum. ‘They have woodland glades and haunts of game.’ Aeineid 3.646-647.: vitam in silvis inter deserta ferarum/ lustra domosque traho. ‘I began to drag out my life in the woods among the lonely lairs and haunts of wild beasts.’ 3.432: canibus resonantia saxa. . . ‘Rocks that echo with her hounds. . .’

|

DSDDDS Elision: plurima habens |

"suetum canibus resonare tubisque": echoes a Virgilian phrase describing Scylla. This is probably a mere echo of diction rather than any deeper, content-based parallel. This is a good example of the pervading influence of the poet's classical background, of the pages and pages memorized during his education, in his Latin versification. MCD | ||

| Sunt in secessu bini montesque propinqui, | The precise locale being described has been exhaustively sought after (cf. Althof ad loc.), but is probably imaginary; the details given are largely taken from the Aeneid and are closely tailored to the series of one-on-one combats that will occur there.

|

Aeineid 1.159-160.: est in secessu longo locus. . .hinc atque hinc vastae rupes geminique minantur/ in caelum scopuli, quorum sub vertice late Aequora tuta silent. . .huc. . .Aeneas. . .subit. ‘There in a deep inlet lies a spot. On either side loom heavenward huge cliffs and twin peaks, beneath whose crest far and wide is the stillness of sheltered water. HereAeneas takes shelter.’ 3.229: in secessu longo. . . ‘In a deep recess. . .’ 8.597-598.: est ingens gelidum lucus prope Caeritis amnem. . .undique colles/ inclusere cavi et nigra nemus abiete cingunt. ‘Near Caere’s cold stream there stands a vast grove; on all sides curving hills enclose it and girdle the woodland with dark fir trees.’ 11.522-523.: est curvo anfractu valles. . .quam densis frondibus atrum/ urget utrimque latus. ‘There is a valley with sweeping curve, hemmed in on either side by a wall black with dense foliage.’

|

SSSSDS | |||

| Inter quos licet angustum specus extat amoenum, | Aeineid 1.159-160.: est in secessu longo locus. . .hinc atque hinc vastae rupes geminique minantur/ in caelum scopuli, quorum sub vertice late Aequora tuta silent. . .huc. . .Aeneas. . .subit. ‘There in a deep inlet lies a spot. On either side loom heavenward huge cliffs and twin peaks, beneath whose crest far and wide is the stillness of sheltered water. HereAeneas takes shelter.’ 3.229: in secessu longo. . . ‘In a deep recess. . .’ 8.597-598.: est ingens gelidum lucus prope Caeritis amnem. . .undique colles/ inclusere cavi et nigra nemus abiete cingunt. ‘Near Caere’s cold stream there stands a vast grove; on all sides curving hills enclose it and girdle the woodland with dark fir trees.’ 11.522-523.: est curvo anfractu valles. . .quam densis frondibus atrum/ urget utrimque latus. ‘There is a valley with sweeping curve, hemmed in on either side by a wall black with dense foliage.’

|

SDSDDS | Though the view is narrow and the place inhabited by wolves and bears, the poet insists that it is "amoenum," pleasant. Indeed, the poet's depiction of the place is almost schizophrenic, as he continues in the next lines to state that it was created by falling rocks (hardly conducive to safe refuge) and that it was best suited for bloody thieves. Nevertheless, the slight vegetation and Walther's relief at the prospect of rest give the place an air of hope. Possibly this conflicted description emphasizes the sense of relief at the prospect of rest and refuge which he intends Walther and Hildegund to feel. MCD | |||

| Non tellure cava factum, sed vertice rupum: | 495 | SDSSDS | ||||

| Apta quidem statio latronibus illa cruentis. | Aeineid 11.522-523.: accommoda fraudi/ armorumque dolis. . . ‘Fit site for the stratagems and deceits of war. . .’

|

DDSDDS | ||||

| Angulus hic virides ac vescas gesserat herbas. | Georgics 3.174-175.: non gramina tantum/ nec vescas salicum frondes. . . ‘Not grass alone or poor willow leaves. . .’ 4.131: vescumque papaver. . . ‘Fine-seeded poppy. . .’

|

DDSSDS | The diction in these lines echoes Virgilian formulae in the Georgics. I suggest that this effect emphasizes the barrenness of the land, contrasting it with the arable fields from which Walther and Hildegund have fled. | |||

| 'huc', mox ut vidit iuvenis, 'huc' inquit 'eamus, | Aeineid 11.530: huc iuvenis nota fertur regione viarum. ‘Hither the warrior hastens by a well-known road.’

|

SSDSDS | Despite the obvious dangers of the place, the fallen rocks do offer some possibilities for defense and shelter. Throughout their journey, Walther and Hildegund have traveled through hidden places (see l. 420: "Atque die saltus arbustaque densa requirens"). MCD | |||

| His iuvat in castris fessum componere corpus.' | Georgics 4.438: defessa. . .componere membra. . . ‘To settle his weary limbs. . .’ 4.189: ubi iam thalamis se composuere. . . ‘When they have laid themselves to rest in their chambers. . .’

|

DSSSDS | ||||

| Nam postquam fugiens Avarum discesserat oris, | 500 | Avarum…oris: i.e., Attila’s city

|

SDDSDS | |||

| Non aliter somni requiem gustaverat idem | DSDSDS | |||||

| Quam super innixus clipeo; vix clauserat orbes. | Orbes equiv. to oculos

|

Walther's larger-than-life heroism is momentarily humanized with the depiction of his exhaustion. The poet allows the reader or listener an impression of how hard Walther has been working to survive and protect Hildegund. Walther then proceeds to doff his armor and thus his identity as a warrior, delegating power to Hildegund. It is quite a surprising move in an epic poem, as a matter of fact, since Walther does not sleep to receive a prophetic utterance. He sleeps because he has human weaknesses. This could be interpreted as another instance of the poet's ironic view of Germanic heroism, but I actually suspect that the scene simply conveys tenderness and trust in the relationship between Walther and Hildegund. MCD | DSDSDS | |||

| Bellica tum demum deponens pondera dixit | Bellica…pondera equiv. to arma

|

Aeineid 10.496: rapiens immania pondera baltei. . . ‘Tearing away the belt’s huge weight. . .’

|

DSSSDS | |||

| Virginis in gremium fusus: 'circumspice caute, | Aeineid 8.406: coniugis infusus gremio. . . ‘Melting in his wife’s arms. . .’

|

DDSSDS | "fusus": a challenging word to translate. Kratz translates the phrase, "while resting the virgin's lap," which preserves English idioms admirably. However, the phrase seems to imply more movement, using the word "fundo" (literally, "to pour") and the accusative of place to which ("in gremium." Moreover, variants of the word "fundo" appear later in the poem to describe brains or innards pouring out of a stabbed warrior (ll. 667, 951, 977, 1018, 1052). Lewis & Short suggest that one translation of "fundo" might include "stretch out," or "scatter." I suggest that the poet is trying to convey that Walther has lain down with his head in Hildegund's lap. Perhaps the most idiomatic translation might be, "having relaxed into the virgin's lap." MCD | |||

| Hiltgunt, et nebulam si tolli videris atram, | 505 | Nebulam: i.e., of dust from an approaching army

|

Aeineid 2.355-356.: lupi ceu/ raptores atra in nebula. . . ‘Like ravening wolves in a black mist. . .’ 8.258: nebulaque ingens specus aestuat atra. ‘Through the mighty cave the mist surges black.’

|

SDSSDS | ||

| Attactu blando me surgere commonitato, | SSSDDS | |||||

| Et licet ingentem conspexeris ire catervam, | DSSDDS | |||||

| Ne excutias somno subito, mi cara, caveto, | Hiltgunt should not wake Waltharius suddenly and thus startle him; since her eyes (acies, line 509) are good, she will be able to see an enemy from far away (and thus still give Waltharius plenty of time to react).

|

Aeineid 2.302: excutior somno.’I shake myself from sleep.’

|

DSDSDS Elision: ne excutias |

|||

| Nam procul hinc acies potis es transmittere puras. | DDDSDS | |||||

| Instanter cunctam circa explora regionem.' | 510 | SSSSDS Elision: circa explora |

Significance of entrusting all this to Hildegund (importance of the female again, in Anderson). Also, why the emphasis on not waking him suddenly. | |||

| Haec ait atque oculos concluserat ipse nitentes | Aeineid 1.297: haec ait et. . . ‘He speaks these words, and. . .’ 1.228: oculos. . .nitentis. . . ‘Her bright eyes. . .’ Liber Hester 15.8: nitentibus oculis. . . ‘With shining eyes. . .’

|

DDSDDS Elision: atque oculos |

||||

| Iamque diu satis optata fruitur requiete. | Aeineid 4.619: optata luce fruatur. ‘May he enjoy the life he longs for.’

|

DDSDDS |