Difference between revisions of "Waltharius941"

(→Gunther again encourages his men, giving Walther some time to rest (941–961)) |

(→Gunther again encourages his men, giving Walther some time to rest (941–961)) |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | ||

| − | |||

| {{Comment|This description of Gunther is in accordance with the overall depiction of Gunther as suffering most of all from the Christian vice of avarice: his first appearance in 441ff. is marked by his urgent desire to reclaim the wealth his kingdom has lost. His avarice makes him arrogant and bold (468, 628, 720, 1295: Gunther described as superbus), affects his ability to reason (530: male sana mente gravatus, “burdened by a not sane mind”; 754 and 1228: dementem, “insane”), and ultimately dooms his efforts (488, 1062, 1092: described as infelix, “unfortunate”). Cf. also the description of Avarice in Prudentius’ Psychomachia 548ff., where it is described as leading men on as if they were blind and deceiving them (hunc lumine adempto ... caecum errare sinit etc.). The poet of the Waltharius in a sense echoes Prudentius by first making avarice a major theme with Gunther’s lament in 869 (instimulatus enim de te est, o saeva cupido!) and going on to describe Gunther as “miserably blinded”. Indeed, Psychomachia 548-550 can be seen to be central to the entire Waltharius: talia per populos edebat funera uictrix / orbis Auaritia, sternens centena uirorum / millia uulneribus uariis (“Such deaths caused victorious Avarice among people all over the world, laying hundreds of thousands of men low with various wounds”). For more in depth discussion of the relation between Gunther’s characterization and Christian and Germanic virtues, see B. Scherello, “Die Darstellung Gunthers im Waltharius,” Mittellateinisches Jahrbuch 21 (1986), 88-90. JJTY}} | | {{Comment|This description of Gunther is in accordance with the overall depiction of Gunther as suffering most of all from the Christian vice of avarice: his first appearance in 441ff. is marked by his urgent desire to reclaim the wealth his kingdom has lost. His avarice makes him arrogant and bold (468, 628, 720, 1295: Gunther described as superbus), affects his ability to reason (530: male sana mente gravatus, “burdened by a not sane mind”; 754 and 1228: dementem, “insane”), and ultimately dooms his efforts (488, 1062, 1092: described as infelix, “unfortunate”). Cf. also the description of Avarice in Prudentius’ Psychomachia 548ff., where it is described as leading men on as if they were blind and deceiving them (hunc lumine adempto ... caecum errare sinit etc.). The poet of the Waltharius in a sense echoes Prudentius by first making avarice a major theme with Gunther’s lament in 869 (instimulatus enim de te est, o saeva cupido!) and going on to describe Gunther as “miserably blinded”. Indeed, Psychomachia 548-550 can be seen to be central to the entire Waltharius: talia per populos edebat funera uictrix / orbis Auaritia, sternens centena uirorum / millia uulneribus uariis (“Such deaths caused victorious Avarice among people all over the world, laying hundreds of thousands of men low with various wounds”). For more in depth discussion of the relation between Gunther’s characterization and Christian and Germanic virtues, see B. Scherello, “Die Darstellung Gunthers im Waltharius,” Mittellateinisches Jahrbuch 21 (1986), 88-90. JJTY}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 37: | Line 36: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | ||

| − | |||

| {{Comment|Cf. the way Gunther’s men are first described (476): viribus insignes animis plerumque probatos (“Distinguished for their strength, their courage often proved”). It is also reminiscent of the opening captatio benevolentiae (rhetorical device used to secure the goodwill of an audience) in Aeneas’ first speech (Aen. 1.198ff): O socii (neque enim ignari sumus ante malorum), o passi grauiora (“O comrades (for we have not been inexperienced before with disasters), you who have suffered worse”). JJTY}} | | {{Comment|Cf. the way Gunther’s men are first described (476): viribus insignes animis plerumque probatos (“Distinguished for their strength, their courage often proved”). It is also reminiscent of the opening captatio benevolentiae (rhetorical device used to secure the goodwill of an audience) in Aeneas’ first speech (Aen. 1.198ff): O socii (neque enim ignari sumus ante malorum), o passi grauiora (“O comrades (for we have not been inexperienced before with disasters), you who have suffered worse”). JJTY}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 56: | Line 54: | ||

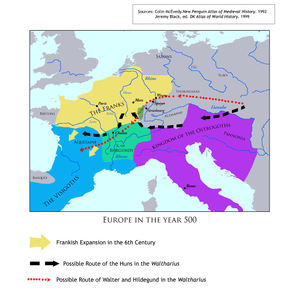

|{{Pictures|[[Image:Europe500.png|center|thumb]]}} | |{{Pictures|[[Image:Europe500.png|center|thumb]]}} | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | ||

| − | |||

| {{Comment|For the pathetic force of the anaphora of sic, see Dido’s final speech in Virgil, Aeneid 4.660: Sed moriamur, ait, sic sic juvat ire per umbras (“‘But let me die,’ she said, ‘thus thus I go gladly down to the shades!’”) Cf. the narrator’s bitter exclamation in 1404: Sic sic armillas partiti sunt Avarenses! (“Thus, thus the men have shared the treasure of the Avars!”) JJTY}} | | {{Comment|For the pathetic force of the anaphora of sic, see Dido’s final speech in Virgil, Aeneid 4.660: Sed moriamur, ait, sic sic juvat ire per umbras (“‘But let me die,’ she said, ‘thus thus I go gladly down to the shades!’”) Cf. the narrator’s bitter exclamation in 1404: Sic sic armillas partiti sunt Avarenses! (“Thus, thus the men have shared the treasure of the Avars!”) JJTY}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 107: | Line 104: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SSSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SSSSDS}} | ||

| − | |||

| {{Comment|The repetition of mors and sanguis in a different case is an instance of the figure polyptoton. sanguem is here used instead of sanguinem as more archaic form, though see Althof 1905 and Beck 1908 ad loc., who remark that the original form should be sanguen. JJTY}} | | {{Comment|The repetition of mors and sanguis in a different case is an instance of the figure polyptoton. sanguem is here used instead of sanguinem as more archaic form, though see Althof 1905 and Beck 1908 ad loc., who remark that the original form should be sanguen. JJTY}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 125: | Line 121: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | ||

| − | |||

| {{Comment|The fact that Gunther’s speech “fires up” his men by his speech ties in to a rich tradition of describing the effects of pathetic rhetoric with of metaphors of fire; see e.g. Cic. De orat. 2.189-190 and Mart. Cap. De nupt. 5.428, where Lady Rhetoric is described as flammatrix (“flamer”). Cf. also Aen. 4.197, where Iarbas is incensed by the words of Rumor concerning Dido and Aeneas: Incenditque animum dictis atque aggerat iras (“With her words she fires his spirit and heaps high his wrath”). The poet of the Waltharius makes especially fruitful use of the metaphor by already including metaphors of fire in Gunther’s speech. There, however, they are used to describe the men’s longing for the gold in 950 and 951 (arsistis, ardete). In this way, the poet manages to closely link avarice and rhetoric, resulting in a frenzy without any regard of one’s own safety (Fecerat immemores vitae simul atque salutis). JJTY}} | | {{Comment|The fact that Gunther’s speech “fires up” his men by his speech ties in to a rich tradition of describing the effects of pathetic rhetoric with of metaphors of fire; see e.g. Cic. De orat. 2.189-190 and Mart. Cap. De nupt. 5.428, where Lady Rhetoric is described as flammatrix (“flamer”). Cf. also Aen. 4.197, where Iarbas is incensed by the words of Rumor concerning Dido and Aeneas: Incenditque animum dictis atque aggerat iras (“With her words she fires his spirit and heaps high his wrath”). The poet of the Waltharius makes especially fruitful use of the metaphor by already including metaphors of fire in Gunther’s speech. There, however, they are used to describe the men’s longing for the gold in 950 and 951 (arsistis, ardete). In this way, the poet manages to closely link avarice and rhetoric, resulting in a frenzy without any regard of one’s own safety (Fecerat immemores vitae simul atque salutis). JJTY}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 143: | Line 138: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | ||

| − | |||

| {{Comment|This passage has a possible reminiscence of the footrace in Aen. 5.315ff. The simile, however, provides a highly effective tone of irony, since the only prize the winner of this race will receive, is to be the first to die. See Althof 1905, ad loc. for a convincing refutation of the claim that this passage provides proof of the existence of tournaments in the ninth century. JJTY}} | | {{Comment|This passage has a possible reminiscence of the footrace in Aen. 5.315ff. The simile, however, provides a highly effective tone of irony, since the only prize the winner of this race will receive, is to be the first to die. See Althof 1905, ad loc. for a convincing refutation of the claim that this passage provides proof of the existence of tournaments in the ninth century. JJTY}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 170: | Line 164: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | ||

| − | |||

| {{Comment|Gunther’s original plan not to allow Walther to catch his breath has failed at this point. Cf. Gunther’s speech to his men in 720ff.: nec respirare sinamus (“Let us ... give him no chance to catch his breath”). They had grossly underestimated Walther’s stamina, as their surprise in 829-30 already indicates: Mirantur Franci, quod non lassesceret heros / Waltharius, cui nulla quies spatiumve dabatur (“The Franks were stunned that Walter, to whom neither rest / Nor respite had been given, did not grow exhausted”). JJTY}} | | {{Comment|Gunther’s original plan not to allow Walther to catch his breath has failed at this point. Cf. Gunther’s speech to his men in 720ff.: nec respirare sinamus (“Let us ... give him no chance to catch his breath”). They had grossly underestimated Walther’s stamina, as their surprise in 829-30 already indicates: Mirantur Franci, quod non lassesceret heros / Waltharius, cui nulla quies spatiumve dabatur (“The Franks were stunned that Walter, to whom neither rest / Nor respite had been given, did not grow exhausted”). JJTY}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

Revision as of 23:59, 29 November 2009

Gunther again encourages his men, giving Walther some time to rest (941–961)

| Tum primum Franci coeperunt forte morari | SSSSDS | |||||

| Et magnis precibus dominum decedere pugna | Aeneid 9.789: excedere pugnae. ‘He withdraws from the fight.’

|

SDDSDS | ||||

| Deposcunt. furit ille miser caecusque profatur: | Aeineid 1.561; 4.364: profatur. ‘She speaks.’

|

SDDSDS | This description of Gunther is in accordance with the overall depiction of Gunther as suffering most of all from the Christian vice of avarice: his first appearance in 441ff. is marked by his urgent desire to reclaim the wealth his kingdom has lost. His avarice makes him arrogant and bold (468, 628, 720, 1295: Gunther described as superbus), affects his ability to reason (530: male sana mente gravatus, “burdened by a not sane mind”; 754 and 1228: dementem, “insane”), and ultimately dooms his efforts (488, 1062, 1092: described as infelix, “unfortunate”). Cf. also the description of Avarice in Prudentius’ Psychomachia 548ff., where it is described as leading men on as if they were blind and deceiving them (hunc lumine adempto ... caecum errare sinit etc.). The poet of the Waltharius in a sense echoes Prudentius by first making avarice a major theme with Gunther’s lament in 869 (instimulatus enim de te est, o saeva cupido!) and going on to describe Gunther as “miserably blinded”. Indeed, Psychomachia 548-550 can be seen to be central to the entire Waltharius: talia per populos edebat funera uictrix / orbis Auaritia, sternens centena uirorum / millia uulneribus uariis (“Such deaths caused victorious Avarice among people all over the world, laying hundreds of thousands of men low with various wounds”). For more in depth discussion of the relation between Gunther’s characterization and Christian and Germanic virtues, see B. Scherello, “Die Darstellung Gunthers im Waltharius,” Mittellateinisches Jahrbuch 21 (1986), 88-90. JJTY | |||

| Quaeso, viri fortes et pectora saepe probata, | Aeineid 2.348-349.: iuvenes, fortissima frustra/ pectora. . . ‘My men, hearts vainly valiant. . .’

|

DSSDDS | Cf. the way Gunther’s men are first described (476): viribus insignes animis plerumque probatos (“Distinguished for their strength, their courage often proved”). It is also reminiscent of the opening captatio benevolentiae (rhetorical device used to secure the goodwill of an audience) in Aeneas’ first speech (Aen. 1.198ff): O socii (neque enim ignari sumus ante malorum), o passi grauiora (“O comrades (for we have not been inexperienced before with disasters), you who have suffered worse”). JJTY | |||

| Ne fors haec cuicumque metum, sed conferat iram. | 945 | SSDSDS | ||||

| Quid mihi, si Vosago sic sic inglorius ibo? | Quid mihi equiv. to Quid videbor esse

|

Aeineid 11.793: patrias remeabo inglorius urbes. ‘I will return inglorious to the cities of my sires.’ 10.52-53.: positis inglorius armis/ exigat hic aevum. ‘Here, laying arms aside, let him live out his inglorious days.’ 4.660: sic, sic iuvat ire. ‘Thus, thus I go gladly.’ Statius, Thebaid 4.82-83.: ne rara movens inglorius iret/ agmina. . . ‘Lest with scant following he should go inglorious. . .’

|

DDSSDS | For the pathetic force of the anaphora of sic, see Dido’s final speech in Virgil, Aeneid 4.660: Sed moriamur, ait, sic sic juvat ire per umbras (“‘But let me die,’ she said, ‘thus thus I go gladly down to the shades!’”) Cf. the narrator’s bitter exclamation in 1404: Sic sic armillas partiti sunt Avarenses! (“Thus, thus the men have shared the treasure of the Avars!”) JJTY | ||

| Mentem quisque meam sibi vindicet. en ego partus | Sibi vindicet: “make his own” Partus equiv. to paratus

|

Liber II Macchabeorum 7.2: parati sumus mori magis quam patrias dei leges praevaricari. ‘We are ready to die rather than to transgress the laws of God, received from our fathers.’

|

SDDDDS | |||

| Ante mori sum, Wormatiam quam talibus actis | DSDSDS | |||||

| Ingrediar. petat hic patriam sine sanguine victor? | DDDDDS | |||||

| Hactenus arsistis hominem spoliare metallis, | 950 | DSDDDS | ||||

| Nunc ardete, viri, fusum mundare cruorem, | SDSSDS | |||||

| Ut mors abstergat mortem, sanguis quoque sanguem, | SSSSDS | The repetition of mors and sanguis in a different case is an instance of the figure polyptoton. sanguem is here used instead of sanguinem as more archaic form, though see Althof 1905 and Beck 1908 ad loc., who remark that the original form should be sanguen. JJTY | ||||

| Soleturque necem sociorum plaga necantis.' | SDDSDS | |||||

| His animum dictis demens incendit et omnes | Aeineid 4.197: incenditque animum dictis atque aggerat iras. ‘With her words she fires his spirit and heaps high his wrath.’

|

DSSSDS | The fact that Gunther’s speech “fires up” his men by his speech ties in to a rich tradition of describing the effects of pathetic rhetoric with of metaphors of fire; see e.g. Cic. De orat. 2.189-190 and Mart. Cap. De nupt. 5.428, where Lady Rhetoric is described as flammatrix (“flamer”). Cf. also Aen. 4.197, where Iarbas is incensed by the words of Rumor concerning Dido and Aeneas: Incenditque animum dictis atque aggerat iras (“With her words she fires his spirit and heaps high his wrath”). The poet of the Waltharius makes especially fruitful use of the metaphor by already including metaphors of fire in Gunther’s speech. There, however, they are used to describe the men’s longing for the gold in 950 and 951 (arsistis, ardete). In this way, the poet manages to closely link avarice and rhetoric, resulting in a frenzy without any regard of one’s own safety (Fecerat immemores vitae simul atque salutis). JJTY | |||

| Fecerat immemores vitae simul atque salutis. | 955 | DDSDDS | ||||

| Ac velut in ludis alium praecurrere quisque | Aeneid 5.315-316.: haec ubi dicta, locum capiunt signoque repente/ corripiunt spatia audito limenque relinquunt,/ effusi nimbo similes. ‘This said, they take their place, and suddenly, the signal heard, dash over the course, and leave the barrier, streaming forth like a storm-cloud.’

|

DSDSDS | This passage has a possible reminiscence of the footrace in Aen. 5.315ff. The simile, however, provides a highly effective tone of irony, since the only prize the winner of this race will receive, is to be the first to die. See Althof 1905, ad loc. for a convincing refutation of the claim that this passage provides proof of the existence of tournaments in the ninth century. JJTY | |||

| Ad mortem studuit, sed semita, ut antea dixi, | Ut antea dixi: cf. line 692 and note.

|

SDSDDS Elision: semita ut |

||||

| Cogebat binos bello decernere solos. | Aeineid 11.218: iubent decernere ferro. ‘They command him to decide the issue by the sword.’

|

SSSSDS | ||||

| Vir tamen illustris dum cunctari videt illos, | DSSSDS | Gunther’s original plan not to allow Walther to catch his breath has failed at this point. Cf. Gunther’s speech to his men in 720ff.: nec respirare sinamus (“Let us ... give him no chance to catch his breath”). They had grossly underestimated Walther’s stamina, as their surprise in 829-30 already indicates: Mirantur Franci, quod non lassesceret heros / Waltharius, cui nulla quies spatiumve dabatur (“The Franks were stunned that Walter, to whom neither rest / Nor respite had been given, did not grow exhausted”). JJTY | ||||

| Vertice distractas suspendit in arbore cristas | 960 | Distractas equiv. to detractas Cristas equiv. to galeam

|

Aeineid 10.834-835.: vulnera siccabat lymphis corpusque levabat/ arboris acclinis trunco. procul aerea ramis/ dependet galea. . .ipse aeger anhelans/ colla fovet. ‘He was staunching his wounds with water, and resting his reclining frame against the trunk of a tree. Nearby his bronze helmet hangs from the boughs. . .He himself, sick and panting, eases his neck.’ Eclogue 1.53: frigus captabis opacum. ‘You shall enjoy the cooling shade.’ 2.8: frigora captant. ‘They court the cool shade.’ Georgics 1.376: patulis captavit naribus auras. ‘With open nostrils he snuffs the breeze.’ Aeineid 9.812-813.: tum toto corpore sudor/ liquitur et piceum (nec respirare potestas)/ flumen agit, fessos quatit aeger anhelitus artus. ‘Then all over his body flows the sweat and runs in pitchy stream, and he has no breathing space; a sickly panting shakes his wearied limbs.’

|

DSSDDS | ||

| Et ventum captans sudorem tersit anhelus. | Aeineid 10.834-835.: vulnera siccabat lymphis corpusque levabat/ arboris acclinis trunco. procul aerea ramis/ dependet galea. . .ipse aeger anhelans/ colla fovet. ‘He was staunching his wounds with water, and resting his reclining frame against the trunk of a tree. Nearby his bronze helmet hangs from the boughs. . .He himself, sick and panting, eases his neck.’ Eclogue 1.53: frigus captabis opacum. ‘You shall enjoy the cooling shade.’ 2.8: frigora captant. ‘They court the cool shade.’ Georgics 1.376: patulis captavit naribus auras. ‘With open nostrils he snuffs the breeze.’ Aeineid 9.812-813.: tum toto corpore sudor/ liquitur et piceum (nec respirare potestas)/ flumen agit, fessos quatit aeger anhelitus artus. ‘Then all over his body flows the sweat and runs in pitchy stream, and he has no breathing space; a sickly panting shakes his wearied limbs.’

|

SSSSDS |