Difference between revisions of "Waltharius436"

(→Gunther, King of the Franks, learns of Walther’s presence on his territory and, despite Hagen’s warnings, decides to pursue him for his treasure (436–488)) |

|||

| (9 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 7.148-149.: ''cum prima lustrabat lampade terras/ orta dies. . . '' ‘When the risen day was lighting the earth with her earliest torch. . .’'' ''12.113-114.: ''Postera vix summos spargebat lumine montis/ orta dies. '' ‘The next dawn was just beginning to sprinkle the mountain tops with light.’ ''Georgics ''3.357:'' Sol pallentis haud umquam discutit umbras.'' ‘Never does the Sun scatter the pale mists.’ 12.669: ''ut primum discussae umbrae. . .'' ‘As soon as the shadows scattered. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | ||

| − | |{{Comment|The "portitor" (ferry-man) is the only non-noble character mentioned in the whole of the poem. There is no clear explanation for why he would bring his fee to the Gunther's court | + | |{{Comment|The "portitor" (ferry-man) is the only non-noble character mentioned in the whole of the poem. There is no clear explanation for why he would bring his fee to the Gunther's court. One possibility is that he is paid directly by the king rather than through his labor. Another is that the fish, as an unfamiliar species, would constitute a "wonder" which the king would want to see. (For further insight into the motif of marvels in medieval literature, see Ziolkowki, Fairy Tales Before Fairy Tales (2007), pp. 184-186.) Either way, the outcome of the ferry-man's conscientiousness is weighty for Walther. His epic battle depends on his choice of ferryman, his choice of fee, and the coincidence that he should have brought a fish previously unknown among the Franks. The poet seems untroubled that his narrative should hang upon such a flimsy plot device. MCD <br /> Filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock was famous for his introduction of the term 'MacGuffin,' essentially an arbitrary vehicle through which to set off the action of his films. Perhaps who the ferryman is or why he heads to Gunther's court is less important than the fact that Walther and his treasure is drawn to Gunther's attention. [AP].}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Regalique]] [[coco]], [[reliquorum]] [[quippe]] [[magistro]], | |[[Regalique]] [[coco]], [[reliquorum]] [[quippe]] [[magistro]], | ||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | ||

|{{Comment|The cook forms a vital part of the court, and this one clearly has accrued great prestige to be called "magister." Germanic society depended heavily on the custom of feasting, sharing food and drink. Beowulf, for example, features several feasts in which past triumphs and defeats are remembered, new alliances are forged, and followers are rewarded. In the context of eating, Germans created and confirmed their cultural identity and cohesion. MCD}} | |{{Comment|The cook forms a vital part of the court, and this one clearly has accrued great prestige to be called "magister." Germanic society depended heavily on the custom of feasting, sharing food and drink. Beowulf, for example, features several feasts in which past triumphs and defeats are remembered, new alliances are forged, and followers are rewarded. In the context of eating, Germans created and confirmed their cultural identity and cohesion. MCD}} | ||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

|[[Detulerat]] [[pisces]], [[quos]] [[vir]] [[dedit]] [[ille]] [[viator]]. | |[[Detulerat]] [[pisces]], [[quos]] [[vir]] [[dedit]] [[ille]] [[viator]]. | ||

| Line 53: | Line 52: | ||

|{{Commentary|''Ab alto'': sc. ''solio'' vel sim. | |{{Commentary|''Ab alto'': sc. ''solio'' vel sim. | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 8.115: ''tum pater Aeneas puppi sic fatur ab alta.'' ‘Then father Aeneas speaks thus from the high stern.’ Statius, ''Thebaid'' 12.641: ''curru sic fatur ab alto. '' ‘He speaks thus from his lofty chariot.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDSSDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment|This is the same Gunther mentioned earlier in the poem (ll. 13-33), who was too young to leave his mother and who later grew up to dissolve all ties with the Huns. We know little of his character at this point, other than the fact that he does not feel bound to honor the treaties his father made with the Huns. It is difficult to interpret Gunther's breach of promise. On | + | | {{Comment|This is the same Gunther mentioned earlier in the poem (ll. 13-33), who was too young to leave his mother and who later grew up to dissolve all ties with the Huns. We know little of his character at this point, other than the fact that he does not feel bound to honor the treaties his father made with the Huns. It is difficult to interpret Gunther's breach of promise. On the one hand, faithfulness to oaths held society together, and the failures of Walther and Hagan to keep their childhood oaths are arguably punished at the end of the Waltharius. On the other hand, subjection was considered shameful, so Gunther's attempt to reinstate his kingly dignity might have been read as praiseworthy. The natural narrative shape of the poem has also led us to think of him as "less than" Hagan, since he was a little boy when Hagan was old enough to be sent as a hostage and become a great warrior. |

Ab alto: presumably from his throne, or perhaps more figuratively, with authority as a king MCD}} | Ab alto: presumably from his throne, or perhaps more figuratively, with authority as a king MCD}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 114: | Line 113: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 5.852: ''talia dicta dabat''. ‘He said such words.’ 3.179: ''remque ordine pando.'' ‘I reveal all in order.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS|elision=causamque ex}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS|elision=causamque ex}} | ||

| − | |{{Comment|The poet's choice of words resembles Virgil's description of Aeneas, when he first receives Apollo's prophecy that he should found a new land in Italy. On waking, he tells Dido, he springs up and carefully retells his prophetic dream to his father ("remque ordine pando"). It is possible that by echoing Aeneas' account in the ferryman's, the poet intends an ironic parallel between Aeneas' and Anchises' joy at the future and Hagan and Gunther's reactions to the news of Walther's presence near Worms. Since Walther needs to return home to found his own successful dynasty, the comparison is apt. MCD}} | + | |{{Comment|The poet's choice of words resembles Virgil's description of Aeneas, when he first receives Apollo's prophecy that he should found a new land in Italy. On waking, he tells Dido, he springs up and carefully retells his prophetic dream to his father ("remque ordine pando"). It is possible that by echoing Aeneas' account in the ferryman's, the poet intends an ironic parallel between Aeneas' and Anchises' joy at the future and Hagan's and Gunther's reactions to the news of Walther's presence near Worms. Since Walther needs to return home to found his own successful dynasty, the comparison is apt. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Vespere]] [[praeterito]] [[residebam]] [[litore]] [[Rheni]] | |[[Vespere]] [[praeterito]] [[residebam]] [[litore]] [[Rheni]] | ||

| Line 141: | Line 140: | ||

|{{Commentary|''Pugnae certum'': “sure he would have a fight” | |{{Commentary|''Pugnae certum'': “sure he would have a fight” | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 4.554: ''iam certus eundi. . .'' ‘Now that he was resolved on going. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 158: | Line 157: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 12.431: ''hastamque coruscat. '' ‘He is brandishing his spear.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment|" | + | | {{Comment|"coruscat": The poet is fond of words that denote shining, sparkling, or flashing. In this case, the sparkle is literally applied to the reflection of the brandished spear. In other cases, however, it denotes fame, beauty, or worth. Thus, Worms is described as "nitentem" (l. 433) and Walther as "coruscus" (l. 525). MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Namque]] [[viro]] [[forti1|forti]] [[similis]] [[fuit]], [[et]] [[licet]] [[ingens]] | |[[Namque]] [[viro]] [[forti1|forti]] [[similis]] [[fuit]], [[et]] [[licet]] [[ingens]] | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 1.589: ''os umerosque deo similis. . . '' ‘Godlike in face and shoulders. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSDDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSDDDS}} | ||

| − | |{{Comment| | + | |{{Comment|To render Walther similar "to a strong man," the poet alters a Virgilian formula in which Aeneas resembles a god What this allusion lacks in rhetorical force, it makes up in historical interest. The poet apparently is trying to create a hero who preserves the classic heroic features while divorcing him from a divine background and placing him firmly in the Christian universe subordinate to the monotheistic God. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Asportaret]] [[onus]], [[gressum]] [[tamen]] [[extulit]] [[acrem1|acrem]]. | |[[Asportaret]] [[onus]], [[gressum]] [[tamen]] [[extulit]] [[acrem1|acrem]]. | ||

| Line 190: | Line 189: | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDSDDS}} | ||

|{{Comment|"Nitore": See note above. | |{{Comment|"Nitore": See note above. | ||

| − | This description of Hildegund echoes the poet's original depiction of her in her father's home. There, she was " | + | This description of Hildegund echoes the poet's original depiction of her in her father's home. There, she was "stemmate formae"; here, "decorata formae." The use of the word "formae" implies symmetry and perfection above mere attraction. Hildegund is the ideal woman, and as such, it is appropriate to "crown" her prematurely in the poem. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Assequitur]] [[calce]]mque [[terit]] [[iam]] [[calce]] [[puella1|puella]]. | |[[Assequitur]] [[calce]]mque [[terit]] [[iam]] [[calce]] [[puella1|puella]]. | ||

| Line 200: | Line 199: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | ||

| − | ||{{Comment|A somewhat problematic line to translate. Kratz writes that Hildegund "matched him stride for stride." This is a good but loose rendering. Literally, the line reads "the girl bruises heel with heel." This translation suggests Hildegund's loyalty and closeness to Walther. Another possibility: "the girl wipes out footprint with footprint." MCD}} | + | ||{{Comment|A somewhat problematic line to translate. Kratz writes that Hildegund "matched him stride for stride." This is a good but loose rendering. Literally, the line reads "the girl bruises heel with heel." This translation suggests Hildegund's loyalty and closeness to Walther. Another possibility: "the girl wipes out footprint with footprint." The phrasing imitates Virgil's Aeneid (V.324). R. Deryk Williams (Aeneid I-VI, 2006) acknowledges the difficulty of the phrase there too, suggesting that it based on Homer's formulation in the Iliad (23.763, in which Odysseus "is treading in Ajax's footsteps before the dust had settled" (420). MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Ipsaque]] [[robustum]] [[rexit]] [[per]] [[lora]] [[caballum]] | |[[Ipsaque]] [[robustum]] [[rexit]] [[per]] [[lora]] [[caballum]] | ||

| Line 225: | Line 224: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SSDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SSDSDS}} | ||

| − | ||{{Comment|sonipes: like cornipes, another word for the horse, Lion. This time the word emphasizes the noise its hooves make. These euphemisms for the horse echo a feature of Germanic and Norse poetic language, the kenning, which describes a well-known noun circuitously. Thus, an Old English word for "ocean" is "hronrad," or "whale-road." Likewise, in Old Norse, gold is called "Otter's Ransom" and "Freya's Tears," among numerous other titles. MCD}} | + | ||{{Comment|sonipes: like cornipes, another word for the horse, Lion. This time the word emphasizes the noise its hooves make. These euphemisms for the horse echo a feature of Germanic and Norse poetic language, the kenning, which describes a well-known noun circuitously. Thus, an Old English word for "ocean" is "hronrad," or "whale-road." Likewise, in Old Norse, gold is called "Otter's Ransom" and "Freya's Tears," among numerous other titles. "Sonipes" could be translated as "sounding-foot" and "cornipes" as "horn-foot." (The words also work metonymically, substituting the part of a horse --- the hoof --- to signify the whole.) Likewise, the description at line 1059 of a wound as a necklace ("torquem") suggests that the poet is remembering the style of German kennings. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Atque]] [[superba]] [[cupit]] [[glomerare]] [[volumina]] [[crurum]], | |[[Atque]] [[superba]] [[cupit]] [[glomerare]] [[volumina]] [[crurum]], | ||

| Line 309: | Line 308: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDDDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDDDDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment|These lines carry powerful rhetorical affect. The reader (or hearer) knows nothing as yet about Gunther’s personality, and may be looking forward to a reunion between the companions Hagan and Walter. The revelation that Gunther, far from promoting good will and solidarity against the Huns, will pose a threat when Walter expects friendship | + | | {{Comment|These lines carry powerful rhetorical affect. The reader (or hearer) knows nothing as yet about Gunther’s personality, and may be looking forward to a reunion between the companions Hagan and Walter. The revelation comes as a shock that Gunther, far from promoting good will and solidarity against the Huns, will pose a threat when Walter expects friendship! Moreover, it becomes immediately clear that Hagan will have to choose between his best friend and his lord, two highly sacred relationships in Germanic culture. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Gazam]], [[quam2|quam]] [[Gibicho]] [[regi1|regi]] [[transmisit]] [[eoo]], | |[[Gazam]], [[quam2|quam]] [[Gibicho]] [[regi1|regi]] [[transmisit]] [[eoo]], | ||

| Line 328: | Line 327: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSDDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment| | + | | {{Comment|Despite being unquestionably greedy and unrighteously avaricious, Gunther does not simply desire money that in no way belongs to him. He is not exactly a thug, though he might behave like one. Gunther feels himself entitled to the Hunnish treasure because he resents the tribute his own father gave to the Huns to establish a treaty. He apparently regards all Hunnish riches as, in some sense, stolen from the Franks and from him. |

| + | "cunctipotens": all-powerful one, presumably God. The singular invocation suggests that Gunther might be Christian, although in general throughout the poem he represents the older, Germanic warrior ethos in all its problematic glory. MCD [Good point: so far as I can remember, the adjective is used solely of the Christian God. The epithet might be useful in dating the poem: check the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae and the Mittellateinisches Worterbuch sub voce. JZ]}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[haec4|Haec]] [[ait]] [[et]] [[mensam]] [[pede]] [[perculit]] [[exiliensque]] | |[[haec4|Haec]] [[ait]] [[et]] [[mensam]] [[pede]] [[perculit]] [[exiliensque]] | ||

| Line 341: | Line 341: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 10.858: ''equum duci iubet.'' ‘He bids his horse be brought.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 386: | Line 386: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | ||

| − | |{{Comment|Gunther has placed Hagan in an almost unbearable position in which he will be forced to betray one of his vows unless he can dissuade the king. Ward argues that | + | |{{Comment|Gunther has placed Hagan in an almost unbearable position in which he will be forced to betray one of his vows unless he can dissuade the king. Ward argues that for breaking his vow Hagan in punished with the loss of his eye and his teeth (Roman Epic, ed. Boyle, 1993). It is difficult to see, however, what Hagan could have done differently. The Waltharius-poet may be attempting to show the limitations of the Germanic warrior-ethos, which in his view limits ethical behavior. MCD}} |

| + | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[Rex]] [[tamen]] [[econtra]] [[nihilominus]] [[instat]] [[et]] [[infit]]: | |[[Rex]] [[tamen]] [[econtra]] [[nihilominus]] [[instat]] [[et]] [[infit]]: | ||

| Line 403: | Line 404: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|: '' | + | |{{Parallel|: ''Aeneid'' 1.101; 8.539; 12.328: ''fortia corpora. . .'' ‘Bodies of the brave. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 412: | Line 413: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|: '' | + | |{{Parallel|: ''Aeneid'' 1.101; 8.539; 12.328: ''fortia corpora. . .'' ‘Bodies of the brave. . .’ |

<br />Prudentius, ''Hamartigenia'' 423: ''. . .squamosum thoraca gerens de pelle colubri. '' ‘. . .Wearing a scaly breast-plate of snakeskin.’ | <br />Prudentius, ''Hamartigenia'' 423: ''. . .squamosum thoraca gerens de pelle colubri. '' ‘. . .Wearing a scaly breast-plate of snakeskin.’ | ||

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | ||

| − | |{{"Squamosus": literally, scaly. | + | |{{Comment|"Squamosus": literally, "scaly." This image not only captures the appearance of closely-woven Germanic corslets but also brings interesting reptilian associations to Hagan and his men. Dragons, traditional symbols of greed, are often described in terms of their impenetrable scales (as in Beowulf, ll. 2574-2680). By putting on scales, Gunther and his men become less than men, half-beasts transformed by greed. Indeed, in medieval literature dragons are occasionally imagined as demonic versions of men. In the late medieval English romance Bevis of Hampton, two greedy and warring lords are transformed by the Devil into dragons and terrorize Germany and Italy.}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[hic2|Hic]] [[tantum1|tantum]] [[gazae]] [[Francis]] [[deducat]] [[ab|ab ]][[oris]]?' | |[[hic2|Hic]] [[tantum1|tantum]] [[gazae]] [[Francis]] [[deducat]] [[ab|ab ]][[oris]]?' | ||

| Line 452: | Line 453: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS|elision=cernere et}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS|elision=cernere et}} | ||

| − | |{{Comment|"imbellum": literally, "unwarlike | + | |{{Comment|"imbellum": literally, "unwarlike." Despite the ferryman's description of the bellicose passenger, Gunther and his men imagine that Walther will be easy to overcome. The disjunction emphasizes further Gunther's overweening pride and greed. This is an instance of dramatic irony on the part of the Waltharius-poet (see Green, Irony in the Medieval Romance, 1979). MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[sed1|Sed]] [[tamen1|tamen]] [[omnimodis]] [[Hagano]] [[prohibere]] [[studebat]], | |[[sed1|Sed]] [[tamen1|tamen]] [[omnimodis]] [[Hagano]] [[prohibere]] [[studebat]], | ||

| Line 468: | Line 469: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SSSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SSSDDS}} | ||

| − | |{{Comment|Kratz translates "infelix" as "ill-starred," a somewhat figurative rendering. Literally, the word | + | |{{Comment|Kratz translates "infelix" as "ill-starred," a somewhat figurative rendering. Literally, the word can denote infertility, as in Virgil's Georgics, 2.237-239 ("intereunt segetes, subit aspera silva, / lappaeque tribolique, interque nitentia culta /infelix lolium et steriles dominantur avena.") It also comes to carry the meaning of unhappiness, even denoting someone who causes unhappiness. This last definition might best describe the troublemaker Gunther, though the word's connotations of infertility also ominously foreshadow Gunther's fate. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

Latest revision as of 14:08, 17 December 2009

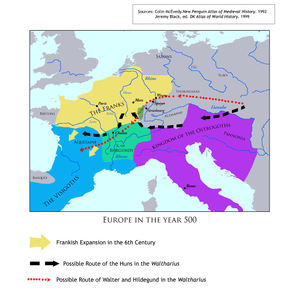

Gunther, King of the Franks, learns of Walther’s presence on his territory and, despite Hagen’s warnings, decides to pursue him for his treasure (436–488)

| Orta dies postquam tenebras discusserat atras, | Aeneid 7.148-149.: cum prima lustrabat lampade terras/ orta dies. . . ‘When the risen day was lighting the earth with her earliest torch. . .’ 12.113-114.: Postera vix summos spargebat lumine montis/ orta dies. ‘The next dawn was just beginning to sprinkle the mountain tops with light.’ Georgics 3.357: Sol pallentis haud umquam discutit umbras. ‘Never does the Sun scatter the pale mists.’ 12.669: ut primum discussae umbrae. . . ‘As soon as the shadows scattered. . .’

|

DSDSDS | "Atras": Coal-black, gloomy, dark. The adjective is associated in classical Latin with words of burning (for example, Aetna) and is never used positively. It usually indicates misfortune, suffering, or at the very least confusion. The fact that Walther spent a "nox atra" should worry a reader: unfortunate times lie ahead for him.

Note the regular DSDSDS scansion, again mimicking the regular marching of the travelers and perhaps also the structured tale retold "ex ordine." MCD | ||||

| Portitor exurgens praefatam venit in urbem | Praefatam (found only in later and juridical Latin) equiv. to supra dictam

|

DSSSDS | The "portitor" (ferry-man) is the only non-noble character mentioned in the whole of the poem. There is no clear explanation for why he would bring his fee to the Gunther's court. One possibility is that he is paid directly by the king rather than through his labor. Another is that the fish, as an unfamiliar species, would constitute a "wonder" which the king would want to see. (For further insight into the motif of marvels in medieval literature, see Ziolkowki, Fairy Tales Before Fairy Tales (2007), pp. 184-186.) Either way, the outcome of the ferry-man's conscientiousness is weighty for Walther. His epic battle depends on his choice of ferryman, his choice of fee, and the coincidence that he should have brought a fish previously unknown among the Franks. The poet seems untroubled that his narrative should hang upon such a flimsy plot device. MCD Filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock was famous for his introduction of the term 'MacGuffin,' essentially an arbitrary vehicle through which to set off the action of his films. Perhaps who the ferryman is or why he heads to Gunther's court is less important than the fact that Walther and his treasure is drawn to Gunther's attention. [AP]. | ||||

| Regalique coco, reliquorum quippe magistro, | SDDSDS | The cook forms a vital part of the court, and this one clearly has accrued great prestige to be called "magister." Germanic society depended heavily on the custom of feasting, sharing food and drink. Beowulf, for example, features several feasts in which past triumphs and defeats are remembered, new alliances are forged, and followers are rewarded. In the context of eating, Germans created and confirmed their cultural identity and cohesion. MCD | |||||

| Detulerat pisces, quos vir dedit ille viator. | Vir…ille viator: i.e., Waltharius

|

DSSDDS | |||||

| Hos dum pigmentis condisset et apposuisset | 440 | Pigmentis: “spices”

|

SSSDDS | The fish is spiced, "pigmentis." The word can also mean painted, which clearly does not apply in this context. However, at line 301, the poet uses the adjective "pigmentatus," which could reasonably be applied to mean "spiced wine" or "painted cups." The use of the word here perhaps suggests that he means spices in the earlier context as well. MCD | |||

| Regi Gunthario, miratus fatur ab alto: | Ab alto: sc. solio vel sim.

|

Aeneid 8.115: tum pater Aeneas puppi sic fatur ab alta. ‘Then father Aeneas speaks thus from the high stern.’ Statius, Thebaid 12.641: curru sic fatur ab alto. ‘He speaks thus from his lofty chariot.’

|

SDSSDS | This is the same Gunther mentioned earlier in the poem (ll. 13-33), who was too young to leave his mother and who later grew up to dissolve all ties with the Huns. We know little of his character at this point, other than the fact that he does not feel bound to honor the treaties his father made with the Huns. It is difficult to interpret Gunther's breach of promise. On the one hand, faithfulness to oaths held society together, and the failures of Walther and Hagan to keep their childhood oaths are arguably punished at the end of the Waltharius. On the other hand, subjection was considered shameful, so Gunther's attempt to reinstate his kingly dignity might have been read as praiseworthy. The natural narrative shape of the poem has also led us to think of him as "less than" Hagan, since he was a little boy when Hagan was old enough to be sent as a hostage and become a great warrior.

Ab alto: presumably from his throne, or perhaps more figuratively, with authority as a king MCD | |||

| Istius ergo modi pisces mihi Francia numquam | Istius ergo modi pisces: Althof characteristically speculates at length about what fish this could be (visually identifiable, edible, found in the Danube region but not in the Rhine) and decides that it must be the huchen. Fishing as recreation was popular among the nobility of the poet’s time. Ergo is here merely a weak intensifier.

|

DDSDDS | |||||

| Ostendit: reor externis a finibus illos. | SDSSDS | ||||||

| Dic mihi quantocius: cuias homo detulit illos?' | Quantocius: “the quicker the better” Cuias homo: “A man of what country?”

|

DDSDDS | Gunther's urgent need to know who brought the fish is difficult to account for apart from the poet's need to bring the king and Walther into collision. MCD | ||||

| Ipseque respondens narrat, quod nauta dedisset. | 445 | Ipse: the cook Nauta: the ferryman (portitor, line 437)

|

DSSSDS | ||||

| Accersire hominem princeps praecepit eundem; | SDSSDS Elision: accersire hominem |

||||||

| Et, cum venisset, de re quaesitus eadem | SSSSDS | ||||||

| Talia dicta dedit causamque ex ordine pandit: | Aeneid 5.852: talia dicta dabat. ‘He said such words.’ 3.179: remque ordine pando. ‘I reveal all in order.’

|

DDSSDS Elision: causamque ex |

The poet's choice of words resembles Virgil's description of Aeneas, when he first receives Apollo's prophecy that he should found a new land in Italy. On waking, he tells Dido, he springs up and carefully retells his prophetic dream to his father ("remque ordine pando"). It is possible that by echoing Aeneas' account in the ferryman's, the poet intends an ironic parallel between Aeneas' and Anchises' joy at the future and Hagan's and Gunther's reactions to the news of Walther's presence near Worms. Since Walther needs to return home to found his own successful dynasty, the comparison is apt. MCD | ||||

| Vespere praeterito residebam litore Rheni | Statius, Silvae 2.5.28: litore Rheni. . . ‘From the banks of the Rhine. . .’

|

DDDSDS | The ferryman's account takes on the qualities of a vision, especially since his description primarily creates an image rather than a narrative of Walther and Hildegund. The poet is creating the poetic equivalent of a film flashback. MCD | ||||

| Conspexique viatorem propere venientem | 450 | SDSDDS | |||||

| Et veluti pugnae certum per membra paratum: | Pugnae certum: “sure he would have a fight”

|

Aeneid 4.554: iam certus eundi. . . ‘Now that he was resolved on going. . .’

|

DSSSDS | The poet emphasizes again Walther's formidable appearance in his armor. In the lines that follow, he enumerates again the items of armor Walther has worn from Pannonia, though this has already been described at ll. 333-340. The reiteration emphasizes Walther's identity as a warrior and the impressive appearance he makes to all who see him. He is the type of a classical or Germanic hero, physically recognizable as greater than other men, and his identity is fused with his warrior spirit. On a more naturalistic level, the reiteration of his armor prepares the reader for Walther's fatigue when he and Hildegund arrive in the Vosges, since he has enacted the warrior role for the entirety of their forty-day journey. MCD | |||

| Aere etenim penitus fuerat, rex inclite, cinctus | DDDSDS Elision: aere etenim |

||||||

| Gesserat et scutum gradiens hastamque coruscam. | Aeneid 12.431: hastamque coruscat. ‘He is brandishing his spear.’

|

DSDSDS | "coruscat": The poet is fond of words that denote shining, sparkling, or flashing. In this case, the sparkle is literally applied to the reflection of the brandished spear. In other cases, however, it denotes fame, beauty, or worth. Thus, Worms is described as "nitentem" (l. 433) and Walther as "coruscus" (l. 525). MCD | ||||

| Namque viro forti similis fuit, et licet ingens | Aeneid 1.589: os umerosque deo similis. . . ‘Godlike in face and shoulders. . .’

|

DSDDDS | To render Walther similar "to a strong man," the poet alters a Virgilian formula in which Aeneas resembles a god What this allusion lacks in rhetorical force, it makes up in historical interest. The poet apparently is trying to create a hero who preserves the classic heroic features while divorcing him from a divine background and placing him firmly in the Christian universe subordinate to the monotheistic God. MCD | ||||

| Asportaret onus, gressum tamen extulit acrem. | 455 | Aeneid 10.553: loricam clipeique ingens onus impedit. ‘He pins the corslet and the shield’s huge burden together.’ 2.753: qua gressum extuleram. ‘. . .By which I had left the city.’

|

SDSDDS | ||||

| Hunc incredibili formae decorata nitore | Liber Hester 2.15: erat enim formonsa valde et incredibili pulchritudine. ‘For she was exceeding fair, and with incredible beauty.’ `

|

SDSDDS | "Nitore": See note above.

This description of Hildegund echoes the poet's original depiction of her in her father's home. There, she was "stemmate formae"; here, "decorata formae." The use of the word "formae" implies symmetry and perfection above mere attraction. Hildegund is the ideal woman, and as such, it is appropriate to "crown" her prematurely in the poem. MCD | ||||

| Assequitur calcemque terit iam calce puella. | Assequitur equiv. to simply sequitur

|

Aeneid 5.324: calcemque terit iam calce. ‘He grazes foot with foot.’

|

DSDSDS | A somewhat problematic line to translate. Kratz writes that Hildegund "matched him stride for stride." This is a good but loose rendering. Literally, the line reads "the girl bruises heel with heel." This translation suggests Hildegund's loyalty and closeness to Walther. Another possibility: "the girl wipes out footprint with footprint." The phrasing imitates Virgil's Aeneid (V.324). R. Deryk Williams (Aeneid I-VI, 2006) acknowledges the difficulty of the phrase there too, suggesting that it based on Homer's formulation in the Iliad (23.763, in which Odysseus "is treading in Ajax's footsteps before the dust had settled" (420). MCD | |||

| Ipsaque robustum rexit per lora caballum | Caballum: the Vulgar Latin word for equus, rare in Classical authors, but the progenitor of French cheval, Spanish caballo, Italian cavallo, etc.

|

DSSSDS | |||||

| Scrinia bina quidem dorso non parva ferentem, | DDSSDS | ||||||

| Quae, dum cervicem sonipes discusserit altam | 460 | SSDSDS | sonipes: like cornipes, another word for the horse, Lion. This time the word emphasizes the noise its hooves make. These euphemisms for the horse echo a feature of Germanic and Norse poetic language, the kenning, which describes a well-known noun circuitously. Thus, an Old English word for "ocean" is "hronrad," or "whale-road." Likewise, in Old Norse, gold is called "Otter's Ransom" and "Freya's Tears," among numerous other titles. "Sonipes" could be translated as "sounding-foot" and "cornipes" as "horn-foot." (The words also work metonymically, substituting the part of a horse --- the hoof --- to signify the whole.) Likewise, the description at line 1059 of a wound as a necklace ("torquem") suggests that the poet is remembering the style of German kennings. MCD | ||||

| Atque superba cupit glomerare volumina crurum, | Glomerare volumina crurum: i.e., to flex its long legs.

|

Georgics 3.117: insultare solo gressus glomerare superbos. ‘. . .To gallop over the earth and round his proud paces.’ 3.192: sinuetque alterna volumina crurum. ‘Let him bend his legs in alternating curves.’

|

DDDDDS | The picture of the perfect hero with the perfect woman is completed by the perfect, sprited horse. The poet creates a strong image. MCD | |||

| Dant sonitum, ceu quis gemmis illiserit aurum. | Aeineid 12.524: dant sonitum spumosi amnes. ‘Foaming rivers roar.’ Statius, Thebaid 5.564: dat sonitum tellus. ‘The earth re-echoes.’

|

DSSSDS | "gemmis": When she is first introduced, Hildegund is described as the "gemma parentum," the jewel of her parents (l. 74). Ward suggests that Hildegund is the true treasure in this scenario, although the vivid and tempting picture the ferryman paints here makes it easy to understand why Gunther misses this moral. MCD | ||||

| Hic mihi praesentes dederat pro munere pisces.' | DSDSDS | ||||||

| His Hagano auditis -- ad mensam quippe resedit -- | DSSSDS Elision: Hagano auditis |

"quippe": emphasizes that Hagan is one of Gunther's closest allies and associates. Wherever the king sits, Hagan sits also. This will increase the gravity of Hagan's dilemma later in the poem. MCD | |||||

| Laetior in medium prompsit de pectore verbum: | 465 | DDSSDS | |||||

| Congaudete mihi quaeso, quia talia novi: | SDSDDS | ||||||

| Waltharius collega meus remeavit ab Hunis.' | DSDDDS | Hagan recognizes his childhood friend immediately by his description. MCD | |||||

| Guntharius princeps ex hac ratione superbus | DSSDDS | ||||||

| Vociferatur, et omnis ei mox aula reclamat: | DDDSDS | ||||||

| Congaudete mihi iubeo, quia talia vixi! | 470 | Iubeo: tellingly replaces Hagen’s humbler quaeso (line 166).

|

SDDDDS | These lines carry powerful rhetorical affect. The reader (or hearer) knows nothing as yet about Gunther’s personality, and may be looking forward to a reunion between the companions Hagan and Walter. The revelation comes as a shock that Gunther, far from promoting good will and solidarity against the Huns, will pose a threat when Walter expects friendship! Moreover, it becomes immediately clear that Hagan will have to choose between his best friend and his lord, two highly sacred relationships in Germanic culture. MCD | |||

| Gazam, quam Gibicho regi transmisit eoo, | Eoo equiv. to orientis, i.e., Hunnorum.

|

SDSSDS | |||||

| Nunc mihi cunctipotens huc in mea regna remisit.' | Cuncipotens: sc. Deus

|

Aeneid 2.543: meque in mea regna remisit. ‘He has sent me back to my realm.’

|

DDSDDS | Despite being unquestionably greedy and unrighteously avaricious, Gunther does not simply desire money that in no way belongs to him. He is not exactly a thug, though he might behave like one. Gunther feels himself entitled to the Hunnish treasure because he resents the tribute his own father gave to the Huns to establish a treaty. He apparently regards all Hunnish riches as, in some sense, stolen from the Franks and from him.

"cunctipotens": all-powerful one, presumably God. The singular invocation suggests that Gunther might be Christian, although in general throughout the poem he represents the older, Germanic warrior ethos in all its problematic glory. MCD [Good point: so far as I can remember, the adjective is used solely of the Christian God. The epithet might be useful in dating the poem: check the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae and the Mittellateinisches Worterbuch sub voce. JZ] | |||

| Haec ait et mensam pede perculit exiliensque | DSDDDS | ||||||

| Ducere equum iubet et sella componere sculpta | Aeneid 10.858: equum duci iubet. ‘He bids his horse be brought.’

|

DDSSDS Elision: ducere equum |

|||||

| Atque omni de plebe viros secum duodenos | 475 | SSDSDS Elision: atque omni |

|||||

| Viribus insignes, animis plerumque probatos | Epistula ad Thessalonicenses 1.2.4: probati sumus a Deo. ‘We are tested by God.’

|

DSDSDS | |||||

| Legerat. inter quos simul ire Haganona iubebat. | DSDDDS Elision: H-ELISION: ire Haganona |

||||||

| Qui memor antiquae fidei sociique prioris | DSDDDS | ||||||

| Nititur a coeptis dominum transvertere rebus. | DSDSDS | Gunther has placed Hagan in an almost unbearable position in which he will be forced to betray one of his vows unless he can dissuade the king. Ward argues that for breaking his vow Hagan in punished with the loss of his eye and his teeth (Roman Epic, ed. Boyle, 1993). It is difficult to see, however, what Hagan could have done differently. The Waltharius-poet may be attempting to show the limitations of the Germanic warrior-ethos, which in his view limits ethical behavior. MCD | |||||

| Rex tamen econtra nihilominus instat et infit: | 480 | Econtra: formed from the preposition and the adverb. Beck gives examples of similar Vulgar Latin combinations that survive in French: de retro (derrière), de intus (dans), de unde (dont).

|

|

DSDDDS | |||

| Ne tardate, viri, praecingite corpora ferro | : Aeneid 1.101; 8.539; 12.328: fortia corpora. . . ‘Bodies of the brave. . .’

|

SDSDDS | |||||

| Fortia, squamosus thorax iam terga recondat. | : Aeneid 1.101; 8.539; 12.328: fortia corpora. . . ‘Bodies of the brave. . .’

|

DSSSDS | "Squamosus": literally, "scaly." This image not only captures the appearance of closely-woven Germanic corslets but also brings interesting reptilian associations to Hagan and his men. Dragons, traditional symbols of greed, are often described in terms of their impenetrable scales (as in Beowulf, ll. 2574-2680). By putting on scales, Gunther and his men become less than men, half-beasts transformed by greed. Indeed, in medieval literature dragons are occasionally imagined as demonic versions of men. In the late medieval English romance Bevis of Hampton, two greedy and warring lords are transformed by the Devil into dragons and terrorize Germany and Italy. | ||||

| Hic tantum gazae Francis deducat ab oris?' | Liber Deuteronomii 1.41: instructi armis. . . ‘Ready armed. . .’ Danihel Propheta 3.22: nam iussio regis urgebat. ‘For the king’s commandment was urgent.’

|

SSSSDS | |||||

| Instructi telis, nam iussio regis adsurget, | SSSDDS | ||||||

| Exibant portis, te Waltharium cupientes | 485 | Te Waltharium: apostrophe.

|

SSSDDS | ||||

| Cernere et imbellem lucris fraudare putantes. | Lucris fraudare equiv. to [se eum] armillis fraudaturos

|

DSSSDS Elision: cernere et |

"imbellum": literally, "unwarlike." Despite the ferryman's description of the bellicose passenger, Gunther and his men imagine that Walther will be easy to overcome. The disjunction emphasizes further Gunther's overweening pride and greed. This is an instance of dramatic irony on the part of the Waltharius-poet (see Green, Irony in the Medieval Romance, 1979). MCD | ||||

| Sed tamen omnimodis Hagano prohibere studebat, | DDDDDS | ||||||

| At rex infelix coeptis resipiscere non vult. | SSSDDS | Kratz translates "infelix" as "ill-starred," a somewhat figurative rendering. Literally, the word can denote infertility, as in Virgil's Georgics, 2.237-239 ("intereunt segetes, subit aspera silva, / lappaeque tribolique, interque nitentia culta /infelix lolium et steriles dominantur avena.") It also comes to carry the meaning of unhappiness, even denoting someone who causes unhappiness. This last definition might best describe the troublemaker Gunther, though the word's connotations of infertility also ominously foreshadow Gunther's fate. MCD |