Difference between revisions of "Waltharius489"

| (20 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | ===Walther makes his camp in a mountainous area and goes to sleep (489–512)=== | ||

{| | {| | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 8: | Line 9: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|"magnanimus": literally, great-souled, great-hearted. Beyond mere kindness or generosity, the word implies heroic greatness of spirit. In this vein, Dante frequently uses an Italian cognate of the word to describe figures who, while damned, retain inherent nobility, such as Virgil or Farinata degli Uberti. MCD [The adjective was a Latin calque upon the Greek megathumos and megalopsuchos, as Servius pointed out in his comment on Aeneid 1.260. Attested first in Ennius, it is a fixture in Latin poetry. JZ]}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Venerat]] [[in]] [[ | + | |[[Venerat]] [[in]] [[saltum]] [[iam]] [[tum]] [[Vosagum]] [[vocitatum]]. |

|490 | |490 | ||

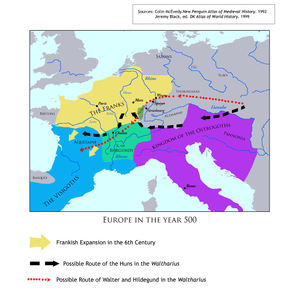

|{{Commentary|''Vosagum'': the name properly belongs not just to a ''saltus'' but to the region of the Vosges Mountains, now in north-eastern France. | |{{Commentary|''Vosagum'': the name properly belongs not just to a ''saltus'' but to the region of the Vosges Mountains, now in north-eastern France. | ||

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Pictures|[[Image:Europe500.png|center|thumb]]}} |

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | | {{Comment|The area around Worms falls outside of the defined modern boundaries of the Vosges. Walther and Hildgund had most likely reached only the northernmost peaks of the mountain range, which are made of sandstone and rise to (comparatively) low heights around 2000 feet. Further south, the mountains become granite and rise much higher. Throughout, they would have been thickly forested, resembling the Black Forest in age and density. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Nam]] [[nemus]] [[est]] [[ingens2|ingens]], [[spatiosum]], [[lustra]] [[ferarum]] | |[[Nam]] [[nemus]] [[est]] [[ingens2|ingens]], [[spatiosum]], [[lustra]] [[ferarum]] | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|''Georgics'' 2.471: ''illic saltus ac lustra ferarum.'' ‘They have woodland glades and haunts of game.’ '' | + | |{{Parallel|''Georgics'' 2.471: ''illic saltus ac lustra ferarum.'' ‘They have woodland glades and haunts of game.’ ''Aeneid'' 3.646-647.: ''vitam in silvis inter deserta ferarum/ lustra domosque traho. '' ‘I began to drag out my life in the woods among the lonely lairs and haunts of wild beasts.’ 3.432: ''canibus resonantia saxa. . .'' ‘Rocks that echo with her hounds. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|The Waltharius-poet creates an odd variant of the classical locus amoenus, in which a beautiful place is described. Indeed, the use of the word "nemus," often associated with sacred groves, would lead us to expect a peaceful or beautiful place. However, this nemus is "ingens," and home to wild beasts. As a place of apparent but deceptive refuge, it has more in common with Virgil's island of the Cyclops, which also is home to "lustra ferarum." MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Plurima]] [[habens]], [[suetum1|suetum]] [[canibus]] [[resonare]] [[tubisque]]. | |[[Plurima]] [[habens]], [[suetum1|suetum]] [[canibus]] [[resonare]] [[tubisque]]. | ||

| Line 32: | Line 33: | ||

|{{Commentary|''Suetum canibus resonare tubisque'': i.e., a popular place for hunting. | |{{Commentary|''Suetum canibus resonare tubisque'': i.e., a popular place for hunting. | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|''Georgics'' 2.471: ''illic saltus ac lustra ferarum.'' ‘They have woodland glades and haunts of game.’ '' | + | |{{Parallel|''Georgics'' 2.471: ''illic saltus ac lustra ferarum.'' ‘They have woodland glades and haunts of game.’ ''Aeneid'' 3.646-647.: ''vitam in silvis inter deserta ferarum/ lustra domosque traho. '' ‘I began to drag out my life in the woods among the lonely lairs and haunts of wild beasts.’ 3.432: ''canibus resonantia saxa. . .'' ‘Rocks that echo with her hounds. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSDDDS|elision=plurima habens}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSDDDS|elision=plurima habens}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|"suetum canibus resonare tubisque": echoes a Virgilian phrase describing Scylla. This is probably a mere echo of diction rather than any deeper, content-based parallel. [Why? Better explain JZ] This is a good example of the pervading influence of the poet's classical background, of the pages and pages memorized during his education, in his Latin versification. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Sunt]] [[in]] [[secessu]] [[ | + | |[[Sunt]] [[in]] [[secessu]] [[bini]] [[montesque]] [[propinqui]], |

| | | | ||

|{{Commentary|The precise locale being described has been exhaustively sought after (cf. Althof ad loc.), but is probably imaginary; the details given are largely taken from the ''Aeneid'' and are closely tailored to the series of one-on-one combats that will occur there. | |{{Commentary|The precise locale being described has been exhaustively sought after (cf. Althof ad loc.), but is probably imaginary; the details given are largely taken from the ''Aeneid'' and are closely tailored to the series of one-on-one combats that will occur there. | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 1.159-160.: ''est in secessu longo locus. . .hinc atque hinc vastae rupes geminique minantur/ in caelum scopuli, quorum sub vertice late Aequora tuta silent. . .huc. . .Aeneas. . .subit. '' ‘There in a deep inlet lies a spot. On either side loom heavenward huge cliffs and twin peaks, beneath whose crest far and wide is the stillness of sheltered water. HereAeneas takes shelter.’ 3.229:'' in secessu longo. . .'' ‘In a deep recess. . .’ 8.597-598.: ''est ingens gelidum lucus prope Caeritis amnem. . .undique colles/ inclusere cavi et nigra nemus abiete cingunt. '' ‘Near Caere’s cold stream there stands a vast grove; on all sides curving hills enclose it and girdle the woodland with dark fir trees.’ 11.522-523.: ''est curvo anfractu valles. . .quam densis frondibus atrum/ urget utrimque latus. '' ‘There is a valley with sweeping curve, hemmed in on either side by a wall black with dense foliage.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 51: | Line 52: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 1.159-160: ''est in secessu longo locus. . .hinc atque hinc vastae rupes geminique minantur/ in caelum scopuli, quorum sub vertice late Aequora tuta silent. . .huc. . .Aeneas. . .subit. '' ‘There in a deep inlet lies a spot. On either side loom heavenward huge cliffs and twin peaks, beneath whose crest far and wide is the stillness of sheltered water. HereAeneas takes shelter.’ 3.229:'' in secessu longo. . .'' ‘In a deep recess. . .’ 8.597-598: ''est ingens gelidum lucus prope Caeritis amnem. . .undique colles/ inclusere cavi et nigra nemus abiete cingunt. '' ‘Near Caere’s cold stream there stands a vast grove; on all sides curving hills enclose it and girdle the woodland with dark fir trees.’ 11.522-523: ''est curvo anfractu valles. . .quam densis frondibus atrum/ urget utrimque latus. '' ‘There is a valley with sweeping curve, hemmed in on either side by a wall black with dense foliage.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDSDDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|Though the place is narrow and inhabited by wolves and bears, the poet insists that it is "amoenum," pleasant. Indeed, his depiction of the place is almost schizophrenic, as he continues in the next lines to state that it was created by falling rocks (hardly conducive to safe refuge) and that it was best suited for bloody thieves. Nevertheless, the slight vegetation and Walther's relief at the prospect of rest give the place an air of hope. Possibly this conflicted description emphasizes the sense of relief at the prospect of rest and refuge which he intends Walther and Hildegund to feel. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Non]] [[tellure]] [[cava]] [[factum]], [[sed1|sed]] [[vertice]] [[rupum]]: | |[[Non]] [[tellure]] [[cava]] [[factum]], [[sed1|sed]] [[vertice]] [[rupum]]: | ||

| Line 68: | Line 69: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 11.522-523: ''accommoda fraudi/ armorumque dolis''. . . ‘Fit site for the stratagems and deceits of war. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 81: | Line 82: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | | {{Comment|The echoes in these lines of Virgilian formulae in the Georgics may serve to emphasize the barrenness of the land, by contrasting it with the arable fields from which Walther and Hildegund have fled.}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |'[[huc]]', [[mox]] [[ut1|ut]] [[vidit1|vidit]] [[iuvenis]], '[[huc]]' [[inquit]] '[[eamus]], |

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 11.530: ''huc iuvenis nota fertur regione viarum. '' ‘Hither the warrior hastens by a well-known road.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SSDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SSDSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|Despite the obvious dangers of the place, the fallen rocks do offer some possibilities for defense and shelter. Throughout their journey, Walther and Hildegund have traveled through hidden places (see l. 420: "Atque die saltus arbustaque densa requirens"). MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[his2|His]] [[iuvat]] [[in]] [[castris]] [[fessum]] [[componere]] [[corpus]].' | |[[his2|His]] [[iuvat]] [[in]] [[castris]] [[fessum]] [[componere]] [[corpus]].' | ||

| Line 106: | Line 107: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Pictures|[[Image:Europe500.png|center|thumb]]}} |

|{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 125: | Line 126: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|Walther's larger-than-life heroism is momentarily humanized with the depiction of his exhaustion. The poet allows the reader or listener an impression of how hard Walther has been working to survive and to protect Hildegund. Walther then proceeds to doff his armor and thus his identity as a warrior, delegating power to Hildegund. In an epic poem it is surprising that Walther sleeps not to receive a prophetic utterance but to respond to human weaknesses. Although the scene could be interpreted as another instance of the poet's ironic view of Germanic heroism, it could instead convey tenderness and trust in the relationship between Walther and Hildegund. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Bellica]] [[tum]] [[demum]] [[deponens]] [[pondera]] [[dixit]] | |[[Bellica]] [[tum]] [[demum]] [[deponens]] [[pondera]] [[dixit]] | ||

| Line 137: | Line 138: | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[ | + | |[[Virginis]] [[in]] [[gremium]] [[fusus]]: '[[circumspice]] [[caute]], |

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 144: | Line 145: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | | {{Comment|"fusus": a challenging word to translate. Kratz translates the phrase, "while resting the virgin's lap," which preserves English idioms admirably. However, the phrase seems to imply more movement, using the word "fundo" (literally, "to pour") and the accusative of place to which ("in gremium"). Moreover, later in the poem (667, 951, 977, 1018, 1052) variants of the word "fundo" describe the pouring out of brains or innards from stabbed warriors. Lewis & Short suggest that one translation of "fundo" might be "stretch out" or "scatter." The poet may mean to indicate that Walther has lain down with his head in Hildegund's lap. The most idiomatic translation might be "having relaxed into the virgin's lap." MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Hiltgunt1|Hiltgunt]], [[et]] [[nebulam]] [[si]] [[tolli]] [[videris1|videris]] [[atram]], | |[[Hiltgunt1|Hiltgunt]], [[et]] [[nebulam]] [[si]] [[tolli]] [[videris1|videris]] [[atram]], | ||

| Line 164: | Line 165: | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Et]] | + | |[[Et]] [[licet]] [[ingentem]] [[conspexeris]] [[ire]] [[catervam]], |

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 176: | Line 177: | ||

|{{Commentary|Hiltgunt should not wake Waltharius suddenly and thus startle him; since her eyes (''acies'', line 509) are good, she will be able to see an enemy from far away (and thus still give Waltharius plenty of time to react). | |{{Commentary|Hiltgunt should not wake Waltharius suddenly and thus startle him; since her eyes (''acies'', line 509) are good, she will be able to see an enemy from far away (and thus still give Waltharius plenty of time to react). | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 2.302: ''excutior somno.''’I shake myself from sleep.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS|elision=ne excutias}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS|elision=ne excutias}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|"caveto:" Walther may be concerned that if he is woken too suddenly, he will react violently. Such vigilance is a commonplace in action films, proof that "a hero never sleeps." |

| + | |||

| + | '''Walther aptly uses the future imperative as in 506 ("commonitato") because he is referring to a conditional event in the future (cf. the future perfect "videris" in 505) - as opposed to "circumspice" in 504, which Hiltgunt is supposed to do right way. [JJTY]'''}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[nam1|Nam]] [[procul]] [[hinc]] [[acies]] [[potis es]] [[transmittere]] [[puras]]. | |[[nam1|Nam]] [[procul]] [[hinc]] [[acies]] [[potis es]] [[transmittere]] [[puras]]. | ||

| Line 196: | Line 199: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SSSSDS|elision=circa explora}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SSSSDS|elision=circa explora}} | ||

| − | | | + | | {{Comment|Walther entrusts Hildegund with the duties of a guard and trusts to her prudence about whether he should be woken. Though Hildegund spends much of the poem in the background, even this small role is unusual for a woman in a heroic poem, and it affirms her value as an agent in the poem, not merely another treasure carried off from the Huns. Ironically, she is the true "gemma" (see note to l. 462), but as such she is not to be classed with the treasure as an object. The Franks will demand "the treasure and the girl," (l. 602) but they, as usual, are in error. For a further discussion, see Ward, in Roman Epic, ed. Boyle, 1993.}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[haec2|Haec]] [[ait1|ait]] [[atque]] [[oculos]] [[concluserat]] [[ipse]] [[nitentes]] | |[[haec2|Haec]] [[ait1|ait]] [[atque]] [[oculos]] [[concluserat]] [[ipse]] [[nitentes]] | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 1.297: ''haec ait et. . .'' ‘He speaks these words, and. . .’ 1.228: ''oculos. . .nitentis. . . '' ‘Her bright eyes. . .’ ''Liber Hester'' 15.8: ''nitentibus oculis. . . '' ‘With shining eyes. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSDDS|elision=atque oculos}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSDDS|elision=atque oculos}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|"oculos nitentes": See note to l. 453. |

| + | See also Matthew 6:22-24: "The light of thy body is thy eye. If thy eye be single, thy whole body shall be lightsome. But if thy eye be evil thy whole body shall be darksome. If then the light that is in thee, be darkness: the darkness itself how great shall it be! No man can serve two masters. For either he will hate the one, and love the other: or he will sustain the one, and despise the other. You cannot serve God and mammon" (Douay-Rheims translation. In Latin, the verses are: "lucerna corporis est oculus si fuerit oculus tuus simplex totum corpus tuum lucidum erit / si autem oculus tuus nequam fuerit totum corpus tuum tenebrosum erit si ergo lumen quod in te est tenebrae sunt tenebrae quantae erunt / nemo potest duobus dominis servire aut enim unum odio habebit et alterum diliget aut unum sustinebit et alterum contemnet non potestis Deo servire et mamonae") Walther's eyes shine, as indeed his "great soul" does. He is contrasted to Gunther's greed. MCD}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[Iamque]] [[diu]] [[satis]] [[optata]] [[fruitur]] [[requiete]]. | |[[Iamque]] [[diu]] [[satis]] [[optata]] [[fruitur]] [[requiete]]. | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 4.619: ''optata luce fruatur.'' ‘May he enjoy the life he longs for.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 222: | Line 226: | ||

|[[Waltharius436|« previous]] | |[[Waltharius436|« previous]] | ||

|{{Outline| | |{{Outline| | ||

| − | * Prologue | + | * [[WalthariusPrologue|Prologue]] |

| − | * Introduction: the Huns (1–12) | + | * [[Waltharius1|Introduction: the Huns (1–12)]] |

* The Huns (13–418) | * The Huns (13–418) | ||

| − | ** The Franks under Gibich surrender to Attila, giving Hagen as a hostage (13–33) | + | ** [[Waltharius13|The Franks under Gibich surrender to Attila, giving Hagen as a hostage (13–33)]] |

| − | ** The Burgundians under Hereric surrender to Attila, giving Hildegund as a hostage (34–74) | + | ** [[Waltharius34|The Burgundians under Hereric surrender to Attila, giving Hildegund as a hostage (34–74)]] |

| − | ** The Aquitainians under Alphere surrender to Attila, giving Walther as a hostage (75–92) | + | ** [[Waltharius75|The Aquitainians under Alphere surrender to Attila, giving Walther as a hostage (75–92)]] |

| − | ** Experience of the hostages at Attila’s court (93–115) | + | ** [[Waltharius93|Experience of the hostages at Attila’s court (93–115)]] |

| − | ** Death of Gibich, flight of Hagen (116–122) | + | ** [[Waltharius116|Death of Gibich, flight of Hagen (116–122)]] |

| − | ** Attila’s queen Ospirin advises her husband to ensure Walther’s loyalty by arranging a marriage (123–141) | + | ** [[Waltharius123|Attila’s queen Ospirin advises her husband to ensure Walther’s loyalty by arranging a marriage (123–141)]] |

| − | ** Walther rejects Attila’s offer of a bride (142–169) | + | ** [[Waltharius142|Walther rejects Attila’s offer of a bride (142–169)]] |

| − | ** Walther leads the army of the Huns to victory in battle (170–214) | + | ** [[Waltharius170|Walther leads the army of the Huns to victory in battle (170–214)]] |

** The Escape (215–418) | ** The Escape (215–418) | ||

| − | *** Walther returns from battle and encounters Hildegund (215–255) | + | *** [[Waltharius215|Walther returns from battle and encounters Hildegund (215–255)]] |

| − | *** Walther reveals to Hildegund his plans for escaping with Attila’s treasure (256–286) | + | *** [[Waltharius256|Walther reveals to Hildegund his plans for escaping with Attila’s treasure (256–286)]] |

| − | *** Walther hosts a luxurious banquet for Attila’s court; eventually all his intoxicated guests fall asleep (287–323) | + | *** [[Waltharius287|Walther hosts a luxurious banquet for Attila’s court; eventually all his intoxicated guests fall asleep (287–323)]] |

| − | *** Flight of Walther and Hildegund from Attila’s court (324–357) | + | *** [[Waltharius324|Flight of Walther and Hildegund from Attila’s court (324–357)]] |

| − | *** The following day, the escape of Walther and Hildegund is discovered by Ospirin (358–379) | + | *** [[Waltharius358|The following day, the escape of Walther and Hildegund is discovered by Ospirin (358–379)]] |

| − | *** Attila is infuriated and vows revenge on Walther, but can find no one willing to dare to pursue him, even for a large reward (380–418) | + | *** [[Waltharius380|Attila is infuriated and vows revenge on Walther, but can find no one willing to dare to pursue him, even for a large reward (380–418)]] |

* The Single Combats (419–1061) | * The Single Combats (419–1061) | ||

** Diplomacy (419–639) | ** Diplomacy (419–639) | ||

| − | *** Flight of Walther and Hildegund to the area of Worms (419–435) | + | *** [[Waltharius419|Flight of Walther and Hildegund to the area of Worms (419–435)]] |

| − | *** Gunther, King of the Franks, learns of Walther’s presence on his territory and, despite Hagen’s warnings, decides to pursue him for his treasure (436–488) | + | *** [[Waltharius436|Gunther, King of the Franks, learns of Walther’s presence on his territory and, despite Hagen’s warnings, decides to pursue him for his treasure (436–488)]] |

*** '''Walther makes his camp in a mountainous area and goes to sleep (489–512)''' | *** '''Walther makes his camp in a mountainous area and goes to sleep (489–512)''' | ||

| − | *** Gunther and his companions approach Walther’s camp; Hagen unsuccessfully tries to dissuade the king from attacking it (513–531) | + | *** [[Waltharius513|Gunther and his companions approach Walther’s camp; Hagen unsuccessfully tries to dissuade the king from attacking it (513–531)]] |

| − | *** Hildegund sees the Franks approaching and wakes Walther, who calms her fears and prepares for battle; he recognizes Hagen from a distance (532–571) | + | *** [[Waltharius532|Hildegund sees the Franks approaching and wakes Walther, who calms her fears and prepares for battle; he recognizes Hagen from a distance (532–571)]] |

| − | *** Hagen persuades Gunther to try diplomacy before using force (571–580) | + | *** [[Waltharius571|Hagen persuades Gunther to try diplomacy before using force (571–580)]] |

| − | *** Camalo is sent as a messenger to Walther, who offers to make Gunther a gift in return for allowing his passage (581–616) | + | *** [[Waltharius581|Camalo is sent as a messenger to Walther, who offers to make Gunther a gift in return for allowing his passage (581–616)]] |

| − | *** Hagen counsels Gunther to accept the offer, but Gunther rejects this advice, calling him a coward. Insulted, Hagen goes off to a nearby hill (617–639) | + | *** [[Waltharius617|Hagen counsels Gunther to accept the offer, but Gunther rejects this advice, calling him a coward. Insulted, Hagen goes off to a nearby hill (617–639)]] |

** Combat (640–1061) | ** Combat (640–1061) | ||

| − | *** 1st single combat: Camalo is sent back to Walther, who slays him (640–685) | + | *** [[Waltharius640|1st single combat: Camalo is sent back to Walther, who slays him (640–685)]] |

| − | *** 2nd single combat: Walther slays Kimo/Scaramund, Camalo’s nephew (686–719) | + | *** [[Waltharius686|2nd single combat: Walther slays Kimo/Scaramund, Camalo’s nephew (686–719)]] |

| − | *** Gunther encourages his men (720–724) | + | *** [[Waltharius720|Gunther encourages his men (720–724)]] |

| − | *** 3rd single combat: Walther slays Werinhard, a descendant of the Trojan Pandarus (725–753) | + | *** [[Waltharius725|3rd single combat: Walther slays Werinhard, a descendant of the Trojan Pandarus (725–753)]] |

| − | *** 4th single combat: Walther slays the Saxon Ekivrid, after an exchange of insults (754–780) | + | *** [[Waltharius754|4th single combat: Walther slays the Saxon Ekivrid, after an exchange of insults (754–780)]] |

| − | *** 5th single combat: Walther slays Hadawart, after an exchange of insults (781–845) | + | *** [[Waltharius781|5th single combat: Walther slays Hadawart, after an exchange of insults (781–845)]] |

| − | *** Hagen sees his nephew Patavrid going off to fight Walther and laments the evil wreaked on mankind by greed (846–877) | + | *** [[Waltharius846|Hagen sees his nephew Patavrid going off to fight Walther and laments the evil wreaked on mankind by greed (846–877)]] |

| − | *** 6th single combat: after trying to dissuade him from fighting, Walther slays Patavrid (878–913) | + | *** [[Waltharius878|6th single combat: after trying to dissuade him from fighting, Walther slays Patavrid (878–913)]] |

| − | *** 7th single combat: Walther slays Gerwitus (914–940) | + | *** [[Waltharius914|7th single combat: Walther slays Gerwitus (914–940)]] |

| − | *** Gunther again encourages his men, giving Walther some time to rest (941–961) | + | *** [[Waltharius941|Gunther again encourages his men, giving Walther some time to rest (941–961)]] |

| − | *** 8th single combat: Walther is shorn of his hair by Randolf, whom he then slays (962–981) | + | *** [[Waltharius962|8th single combat: Walther is shorn of his hair by Randolf, whom he then slays (962–981)]] |

| − | *** Walther is attacked by Eleuthir/Helmnot, assisted by Trogus, Tanastus, and Gunther; he slays all but Gunther (981–1061) | + | *** [[Waltharius981|Walther is attacked by Eleuthir/Helmnot, assisted by Trogus, Tanastus, and Gunther; he slays all but Gunther (981–1061)]] |

* The Final Combat (1062–1452) | * The Final Combat (1062–1452) | ||

| − | ** Gunther tries to persuade Hagen to help him to defeat Waltharius; remembering his wounded honor, Hagen refuses (1062–1088) | + | ** [[Waltharius1062|Gunther tries to persuade Hagen to help him to defeat Waltharius; remembering his wounded honor, Hagen refuses (1062–1088)]] |

| − | ** Hagen changes his mind and agrees to help Gunther, but advises that they must lie low wait until Walther comes down from the mountains into open ground (1089–1129) | + | ** [[Waltharius1089|Hagen changes his mind and agrees to help Gunther, but advises that they must lie low wait until Walther comes down from the mountains into open ground (1089–1129)]] |

| − | ** Walther decides to spend the night in the mountains. He rematches the severed heads with the bodies of his victims, prays for their souls, then sleeps (1130–1187) | + | ** [[Waltharius1130|Walther decides to spend the night in the mountains. He rematches the severed heads with the bodies of his victims, prays for their souls, then sleeps (1130–1187)]] |

| − | ** The following day, Walther and Hildegund set out from the mountains, taking the horses and arms of the defeated warriors (1188–1207) | + | ** [[Waltharius1188|The following day, Walther and Hildegund set out from the mountains, taking the horses and arms of the defeated warriors (1188–1207)]] |

| − | ** Hildegund perceives Gunther and Hagen approaching to attack; the king addresses Walther (1208–1236) | + | ** [[Waltharius1208|Hildegund perceives Gunther and Hagen approaching to attack; the king addresses Walther (1208–1236)]] |

| − | ** Walther ignores Gunther and pleads with Hagen to remember the bond of their childhood friendship; Hagen counters that Walther has already broken their faith by slaying Patavrid (1237–1279) | + | ** [[Waltharius1237|Walther ignores Gunther and pleads with Hagen to remember the bond of their childhood friendship; Hagen counters that Walther has already broken their faith by slaying Patavrid (1237–1279)]] |

| − | ** The fight begins and continues for seven hours; Gunther foolishly tries to retrieve a thrown spear from the ground near Walther and is only saved from death by Hagen’s brave intervention (1280–1345) | + | ** [[Waltharius1280|The fight begins and continues for seven hours; Gunther foolishly tries to retrieve a thrown spear from the ground near Walther and is only saved from death by Hagen’s brave intervention (1280–1345)]] |

| − | ** Walther challenges Hagen; he severs Gunther’s leg, but Hagen again saves the king’s life (1346–1375) | + | ** [[Waltharius1346|Walther challenges Hagen; he severs Gunther’s leg, but Hagen again saves the king’s life (1346–1375)]] |

| − | ** Hagen cuts off Walther’s right hand; Walther gouges out one of Hagen’s eyes and, cutting open his cheek, knocks out four teeth (1376–1395) | + | ** [[Waltharius1376|Hagen cuts off Walther’s right hand; Walther gouges out one of Hagen’s eyes and, cutting open his cheek, knocks out four teeth (1376–1395)]] |

| − | ** Having wounded each other, the warriors end the battle, drink together, and engage in a friendly exchange of humorous taunt (1396–1442) | + | ** [[Waltharius1396|Having wounded each other, the warriors end the battle, drink together, and engage in a friendly exchange of humorous taunt (1396–1442)]] |

| − | ** The warriors return to their respective homes; Walther marries Hildegund and eventually becomes king of the Aquitainians (1443–1452) | + | ** [[Waltharius1443|The warriors return to their respective homes; Walther marries Hildegund and eventually becomes king of the Aquitainians (1443–1452)]] |

| − | * Epilogue (1453–1456)}} | + | * [[Waltharius1453|Epilogue (1453–1456)]]}} |

| | | | ||

|[[Waltharius513|next »]] | |[[Waltharius513|next »]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:12, 17 December 2009

Walther makes his camp in a mountainous area and goes to sleep (489–512)

| Interea vir magnanimus de flumine pergens | Vir magnanimus: Waltharius

|

DSDSDS | "magnanimus": literally, great-souled, great-hearted. Beyond mere kindness or generosity, the word implies heroic greatness of spirit. In this vein, Dante frequently uses an Italian cognate of the word to describe figures who, while damned, retain inherent nobility, such as Virgil or Farinata degli Uberti. MCD [The adjective was a Latin calque upon the Greek megathumos and megalopsuchos, as Servius pointed out in his comment on Aeneid 1.260. Attested first in Ennius, it is a fixture in Latin poetry. JZ] | |||

| Venerat in saltum iam tum Vosagum vocitatum. | 490 | Vosagum: the name properly belongs not just to a saltus but to the region of the Vosges Mountains, now in north-eastern France.

|

DSSDDS | The area around Worms falls outside of the defined modern boundaries of the Vosges. Walther and Hildgund had most likely reached only the northernmost peaks of the mountain range, which are made of sandstone and rise to (comparatively) low heights around 2000 feet. Further south, the mountains become granite and rise much higher. Throughout, they would have been thickly forested, resembling the Black Forest in age and density. MCD | ||

| Nam nemus est ingens, spatiosum, lustra ferarum | Georgics 2.471: illic saltus ac lustra ferarum. ‘They have woodland glades and haunts of game.’ Aeneid 3.646-647.: vitam in silvis inter deserta ferarum/ lustra domosque traho. ‘I began to drag out my life in the woods among the lonely lairs and haunts of wild beasts.’ 3.432: canibus resonantia saxa. . . ‘Rocks that echo with her hounds. . .’

|

DSDSDS | The Waltharius-poet creates an odd variant of the classical locus amoenus, in which a beautiful place is described. Indeed, the use of the word "nemus," often associated with sacred groves, would lead us to expect a peaceful or beautiful place. However, this nemus is "ingens," and home to wild beasts. As a place of apparent but deceptive refuge, it has more in common with Virgil's island of the Cyclops, which also is home to "lustra ferarum." MCD | |||

| Plurima habens, suetum canibus resonare tubisque. | Suetum canibus resonare tubisque: i.e., a popular place for hunting.

|

Georgics 2.471: illic saltus ac lustra ferarum. ‘They have woodland glades and haunts of game.’ Aeneid 3.646-647.: vitam in silvis inter deserta ferarum/ lustra domosque traho. ‘I began to drag out my life in the woods among the lonely lairs and haunts of wild beasts.’ 3.432: canibus resonantia saxa. . . ‘Rocks that echo with her hounds. . .’

|

DSDDDS Elision: plurima habens |

"suetum canibus resonare tubisque": echoes a Virgilian phrase describing Scylla. This is probably a mere echo of diction rather than any deeper, content-based parallel. [Why? Better explain JZ] This is a good example of the pervading influence of the poet's classical background, of the pages and pages memorized during his education, in his Latin versification. MCD | ||

| Sunt in secessu bini montesque propinqui, | The precise locale being described has been exhaustively sought after (cf. Althof ad loc.), but is probably imaginary; the details given are largely taken from the Aeneid and are closely tailored to the series of one-on-one combats that will occur there.

|

Aeneid 1.159-160.: est in secessu longo locus. . .hinc atque hinc vastae rupes geminique minantur/ in caelum scopuli, quorum sub vertice late Aequora tuta silent. . .huc. . .Aeneas. . .subit. ‘There in a deep inlet lies a spot. On either side loom heavenward huge cliffs and twin peaks, beneath whose crest far and wide is the stillness of sheltered water. HereAeneas takes shelter.’ 3.229: in secessu longo. . . ‘In a deep recess. . .’ 8.597-598.: est ingens gelidum lucus prope Caeritis amnem. . .undique colles/ inclusere cavi et nigra nemus abiete cingunt. ‘Near Caere’s cold stream there stands a vast grove; on all sides curving hills enclose it and girdle the woodland with dark fir trees.’ 11.522-523.: est curvo anfractu valles. . .quam densis frondibus atrum/ urget utrimque latus. ‘There is a valley with sweeping curve, hemmed in on either side by a wall black with dense foliage.’

|

SSSSDS | |||

| Inter quos licet angustum specus extat amoenum, | Aeneid 1.159-160: est in secessu longo locus. . .hinc atque hinc vastae rupes geminique minantur/ in caelum scopuli, quorum sub vertice late Aequora tuta silent. . .huc. . .Aeneas. . .subit. ‘There in a deep inlet lies a spot. On either side loom heavenward huge cliffs and twin peaks, beneath whose crest far and wide is the stillness of sheltered water. HereAeneas takes shelter.’ 3.229: in secessu longo. . . ‘In a deep recess. . .’ 8.597-598: est ingens gelidum lucus prope Caeritis amnem. . .undique colles/ inclusere cavi et nigra nemus abiete cingunt. ‘Near Caere’s cold stream there stands a vast grove; on all sides curving hills enclose it and girdle the woodland with dark fir trees.’ 11.522-523: est curvo anfractu valles. . .quam densis frondibus atrum/ urget utrimque latus. ‘There is a valley with sweeping curve, hemmed in on either side by a wall black with dense foliage.’

|

SDSDDS | Though the place is narrow and inhabited by wolves and bears, the poet insists that it is "amoenum," pleasant. Indeed, his depiction of the place is almost schizophrenic, as he continues in the next lines to state that it was created by falling rocks (hardly conducive to safe refuge) and that it was best suited for bloody thieves. Nevertheless, the slight vegetation and Walther's relief at the prospect of rest give the place an air of hope. Possibly this conflicted description emphasizes the sense of relief at the prospect of rest and refuge which he intends Walther and Hildegund to feel. MCD | |||

| Non tellure cava factum, sed vertice rupum: | 495 | SDSSDS | ||||

| Apta quidem statio latronibus illa cruentis. | Aeneid 11.522-523: accommoda fraudi/ armorumque dolis. . . ‘Fit site for the stratagems and deceits of war. . .’

|

DDSDDS | ||||

| Angulus hic virides ac vescas gesserat herbas. | Georgics 3.174-175.: non gramina tantum/ nec vescas salicum frondes. . . ‘Not grass alone or poor willow leaves. . .’ 4.131: vescumque papaver. . . ‘Fine-seeded poppy. . .’

|

DDSSDS | The echoes in these lines of Virgilian formulae in the Georgics may serve to emphasize the barrenness of the land, by contrasting it with the arable fields from which Walther and Hildegund have fled. | |||

| 'huc', mox ut vidit iuvenis, 'huc' inquit 'eamus, | Aeneid 11.530: huc iuvenis nota fertur regione viarum. ‘Hither the warrior hastens by a well-known road.’

|

SSDSDS | Despite the obvious dangers of the place, the fallen rocks do offer some possibilities for defense and shelter. Throughout their journey, Walther and Hildegund have traveled through hidden places (see l. 420: "Atque die saltus arbustaque densa requirens"). MCD | |||

| His iuvat in castris fessum componere corpus.' | Georgics 4.438: defessa. . .componere membra. . . ‘To settle his weary limbs. . .’ 4.189: ubi iam thalamis se composuere. . . ‘When they have laid themselves to rest in their chambers. . .’

|

DSSSDS | ||||

| Nam postquam fugiens Avarum discesserat oris, | 500 | Avarum…oris: i.e., Attila’s city

|

SDDSDS | |||

| Non aliter somni requiem gustaverat idem | DSDSDS | |||||

| Quam super innixus clipeo; vix clauserat orbes. | Orbes equiv. to oculos

|

DSDSDS | Walther's larger-than-life heroism is momentarily humanized with the depiction of his exhaustion. The poet allows the reader or listener an impression of how hard Walther has been working to survive and to protect Hildegund. Walther then proceeds to doff his armor and thus his identity as a warrior, delegating power to Hildegund. In an epic poem it is surprising that Walther sleeps not to receive a prophetic utterance but to respond to human weaknesses. Although the scene could be interpreted as another instance of the poet's ironic view of Germanic heroism, it could instead convey tenderness and trust in the relationship between Walther and Hildegund. MCD | |||

| Bellica tum demum deponens pondera dixit | Bellica…pondera equiv. to arma

|

Aeineid 10.496: rapiens immania pondera baltei. . . ‘Tearing away the belt’s huge weight. . .’

|

DSSSDS | |||

| Virginis in gremium fusus: 'circumspice caute, | Aeineid 8.406: coniugis infusus gremio. . . ‘Melting in his wife’s arms. . .’

|

DDSSDS | "fusus": a challenging word to translate. Kratz translates the phrase, "while resting the virgin's lap," which preserves English idioms admirably. However, the phrase seems to imply more movement, using the word "fundo" (literally, "to pour") and the accusative of place to which ("in gremium"). Moreover, later in the poem (667, 951, 977, 1018, 1052) variants of the word "fundo" describe the pouring out of brains or innards from stabbed warriors. Lewis & Short suggest that one translation of "fundo" might be "stretch out" or "scatter." The poet may mean to indicate that Walther has lain down with his head in Hildegund's lap. The most idiomatic translation might be "having relaxed into the virgin's lap." MCD | |||

| Hiltgunt, et nebulam si tolli videris atram, | 505 | Nebulam: i.e., of dust from an approaching army

|

Aeineid 2.355-356.: lupi ceu/ raptores atra in nebula. . . ‘Like ravening wolves in a black mist. . .’ 8.258: nebulaque ingens specus aestuat atra. ‘Through the mighty cave the mist surges black.’

|

SDSSDS | ||

| Attactu blando me surgere commonitato, | SSSDDS | |||||

| Et licet ingentem conspexeris ire catervam, | DSSDDS | |||||

| Ne excutias somno subito, mi cara, caveto, | Hiltgunt should not wake Waltharius suddenly and thus startle him; since her eyes (acies, line 509) are good, she will be able to see an enemy from far away (and thus still give Waltharius plenty of time to react).

|

Aeneid 2.302: excutior somno.’I shake myself from sleep.’

|

DSDSDS Elision: ne excutias |

"caveto:" Walther may be concerned that if he is woken too suddenly, he will react violently. Such vigilance is a commonplace in action films, proof that "a hero never sleeps."

Walther aptly uses the future imperative as in 506 ("commonitato") because he is referring to a conditional event in the future (cf. the future perfect "videris" in 505) - as opposed to "circumspice" in 504, which Hiltgunt is supposed to do right way. [JJTY] | ||

| Nam procul hinc acies potis es transmittere puras. | DDDSDS | |||||

| Instanter cunctam circa explora regionem.' | 510 | SSSSDS Elision: circa explora |

Walther entrusts Hildegund with the duties of a guard and trusts to her prudence about whether he should be woken. Though Hildegund spends much of the poem in the background, even this small role is unusual for a woman in a heroic poem, and it affirms her value as an agent in the poem, not merely another treasure carried off from the Huns. Ironically, she is the true "gemma" (see note to l. 462), but as such she is not to be classed with the treasure as an object. The Franks will demand "the treasure and the girl," (l. 602) but they, as usual, are in error. For a further discussion, see Ward, in Roman Epic, ed. Boyle, 1993. | |||

| Haec ait atque oculos concluserat ipse nitentes | Aeneid 1.297: haec ait et. . . ‘He speaks these words, and. . .’ 1.228: oculos. . .nitentis. . . ‘Her bright eyes. . .’ Liber Hester 15.8: nitentibus oculis. . . ‘With shining eyes. . .’

|

DDSDDS Elision: atque oculos |

"oculos nitentes": See note to l. 453.

See also Matthew 6:22-24: "The light of thy body is thy eye. If thy eye be single, thy whole body shall be lightsome. But if thy eye be evil thy whole body shall be darksome. If then the light that is in thee, be darkness: the darkness itself how great shall it be! No man can serve two masters. For either he will hate the one, and love the other: or he will sustain the one, and despise the other. You cannot serve God and mammon" (Douay-Rheims translation. In Latin, the verses are: "lucerna corporis est oculus si fuerit oculus tuus simplex totum corpus tuum lucidum erit / si autem oculus tuus nequam fuerit totum corpus tuum tenebrosum erit si ergo lumen quod in te est tenebrae sunt tenebrae quantae erunt / nemo potest duobus dominis servire aut enim unum odio habebit et alterum diliget aut unum sustinebit et alterum contemnet non potestis Deo servire et mamonae") Walther's eyes shine, as indeed his "great soul" does. He is contrasted to Gunther's greed. MCD | |||

| Iamque diu satis optata fruitur requiete. | Aeneid 4.619: optata luce fruatur. ‘May he enjoy the life he longs for.’

|

DDSDDS |