Difference between revisions of "Waltharius1"

| (24 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

|{{Pictures|[[image:Waltharius-Line-1.png|center|thumb]]}} | |{{Pictures|[[image:Waltharius-Line-1.png|center|thumb]]}} | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | | {{Comment|The opening line of the poem refers to the ancient notion "that the whole earth consists of three divisions, Europe, Asia, and Libya" (Herodotus, 2.16). Not only does it set the general stage of action for the poem (which is Europe) but it is also reminiscent of the opening to Caesar's "De Bello Gallico", "Gallia est omnes divisa in patres tres" (All of Gaul is divided into three parts). The author did not know Greek, however, and most likely was not familiar with Caesar's work. Isidore of Seville's Etymologies XIV.2 was probably more influential, "Divisus est autem trifarie: e quibus una pars Asia, altera Europa, tertia Africa nuncupatur" (It is divided into three parts, one of which is called Asia, the second part Europe, the third Africa). <br />"Fratres": not only does the address "brothers" suggest the possibility of the poem's intended monastic audience, it is also one of the few times in the poem the reader is addressed directly. There is the possibility as well that "fratres" could be taken in the sense of universal brotherhood and would hence include women. |

| + | |||

| + | '''Edoardo D'Angelo (1991, p. 166-167) sees here the influence of Lucan, and quotes 9.411-417 from the Bellum Civile: "tertia pars rerum Libye, si credere famae / cuncta uelis; at, si uentos caelumque sequaris, / pars erit Europae. nec enim plus litora Nili / quam Scythicus Tanais primis a Gadibus absunt, / unde Europa fugit Libyen et litora flexu / Oceano fecere locum; sed maior in unam / orbis abit Asiam." JJTY''' '''For the wording of the first half line, the likeliest source of inspiration would be Ovid, Metamorphoses 6.372 "agitur pars tertia mundi" (noted recently by Ruben Florio [2002, p. 3]) JZ'''}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[Moribus]] [[ac]] [[linguis]] [[varias]] [[et]] [[nomine]] [[gentes]] | |[[Moribus]] [[ac]] [[linguis]] [[varias]] [[et]] [[nomine]] [[gentes]] | ||

| Line 28: | Line 30: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SSSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SSSDDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment| "cultu": As distinguished from "religione", it probably can be translated as 'way of life', in the sense of the general style of societal customs, e.g. how they stack their hay, construct and decorate their barns, etc...}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Inter]] [[quas]] [[gens]] [[Pannoniae1|Pannoniae]] [[residere]] [[probatur]], | |[[Inter]] [[quas]] [[gens]] [[Pannoniae1|Pannoniae]] [[residere]] [[probatur]], | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Commentary|''Pannonia'': Roman province in the north-west Balkans, according to the poet the homeland of the “Huns” (''Hunos'', line 5), a nomadic tribe that invaded Europe from the east, beginning around 370 A.D. | + | |{{Commentary|''Pannonia'': Roman province in the north-west Balkans, according to the poet the homeland of the “Huns” (''Hunos'', line 5), a nomadic tribe that invaded Europe from the east, beginning around 370 A.D. |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 45: | Line 47: | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | | {{Comment|"Hunos": The Huns first swept into Roman consciousness when, invading from the east, they displaced the Goths, who, as detailed by Ammianus Marcellinus, ended up decimating the Roman army at the Battle of Adrianople, now Edirne in northwest Turkey, in A.D. 378. The province of Pannonia from line 4 was actually ceded to the Huns in the mid-5th century by the Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II after several major military defeats.}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[hic2|Hic]] [[populus]] [[fortis1|fortis]] [[virtute]] [[vigebat]] [[et]] [[armis]], | |[[hic2|Hic]] [[populus]] [[fortis1|fortis]] [[virtute]] [[vigebat]] [[et]] [[armis]], | ||

| Line 53: | Line 55: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment| Indeed, the Huns were a nomadic people who flourished not by building cities but by military prowess. Note how the Huns left no literary record nor any real archaeological one beyond military equipment.}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Non]] [[circumpositas]] [[solum]] [[domitans]] [[regiones]], | |[[Non]] [[circumpositas]] [[solum]] [[domitans]] [[regiones]], | ||

| Line 72: | Line 74: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment| "oceani": 'Oceanus' in traditional mythology was the son of Uranus and Gaia and the personification of the great river that encircled the known world. Though the extent to which a Carolingian or near-Carolingian monk would have known geography beyond antiquity's understanding of it is unclear, the very same section of Isidore's Etymologies referenced in line 1 explicitly mentions Oceanus as encircling the globe. The Huns were a people of the inland steppes and plains. At the height of its power, the Hunnic Empire stretched from the Caspian and Black Seas to the North Sea and even the Adriatic, but never all the way to the Atlantic Ocean.}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Foedera]] [[supplicibus]] [[donans]] [[sternensque]] [[rebelles1|rebelles]]. | |[[Foedera]] [[supplicibus]] [[donans]] [[sternensque]] [[rebelles1|rebelles]]. | ||

| Line 81: | Line 83: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment| The poet here does not borrow any of the exact language of Aeneid, most notably at 6.852 yet also at 1.257-258, but he does not need to. The allusion to the Virgilian and Roman dictum to "spare the vanquished and crush the proud," an ideal for the imperial Roman leader, is overt. By ascribing this very Roman and ipso facto admirable trait to Attila and the Huns, the poet departs from the view in the ancient Roman's mind of the Huns the scourge of the Roman Empire. <br />This characteristic is factually accurate. Attila and the Huns destroyed many enemy armies, yet they also spared defeated foes in order to exact tribute from them. Indeed, at the very gates of Rome Attila is said to have turned back at the sight of Pope Leo I.}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Ultra]] [[millenos]] [[fertur]] [[dominarier]] [[annos]]. | |[[Ultra]] [[millenos]] [[fertur]] [[dominarier]] [[annos]]. | ||

| Line 90: | Line 92: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SSSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SSSDDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment| This is a case of hyperbole by the author. Perhaps in the medieval mind the name Huns is a reference to an amalgamation of particular antique peripheral invaders, which might explain the reference in line 12 to Attila's wish to renew the "antiquos triumphos." In actuality the Hunnic empire came into existence in the west around 370 when they destroyed a tribe of Alans, and eventually petered out around 469 at the death of Dengizik, the succesor of Attila's son Ellak. <br />Beginning here, but continued throughout the poem, the poet treats the Huns not as barbarians invaders but a strong, proud people with an illustrious history. By putting the Huns on relative par with the Romans (c. line 11) in the way they rule and duration of their "imperium", he strengthens the foundations of his own civilization. Were the Franks and other western European peoples defeated by a mere marauding hoard, there would be no nobility in recalling such story. However, given that the Huns are set up as a broad and powerful civilization, that they were eventually overcome becomes so much more impressive and heroic genesis of the poet's own times.}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Attila1|Attila]] [[rex]] [[quodam1|quodam]] [[tulit]] [[illud1|illud]] [[tempore]] [[regnum]], | |[[Attila1|Attila]] [[rex]] [[quodam1|quodam]] [[tulit]] [[illud1|illud]] [[tempore]] [[regnum]], | ||

| Line 108: | Line 110: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSDDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSDDDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment| "antiquos triumphos": c. note on line 10; most likely "antiquos" should be read as 'ancient' or 'ancestral' as opposed to 'old', which would lend itself to the grandeur with which the poet tries to infuse the Huns. Attila is not attempting to rekindle the fame of his own younger days, but the younger days of his people.}} |

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 116: | Line 118: | ||

|[[WalthariusPrologue|« previous]] | |[[WalthariusPrologue|« previous]] | ||

|{{Outline| | |{{Outline| | ||

| − | * Prologue | + | * [[WalthariusPrologue|Prologue]] |

* '''Introduction: the Huns (1–12)''' | * '''Introduction: the Huns (1–12)''' | ||

* The Huns (13–418) | * The Huns (13–418) | ||

| − | ** The Franks under Gibich surrender to Attila, giving Hagen as a hostage (13–33) | + | ** [[Waltharius13|The Franks under Gibich surrender to Attila, giving Hagen as a hostage (13–33)]] |

| − | ** The Burgundians under Hereric surrender to Attila, giving Hildegund as a hostage (34–74) | + | ** [[Waltharius34|The Burgundians under Hereric surrender to Attila, giving Hildegund as a hostage (34–74)]] |

| − | ** The Aquitainians under Alphere surrender to Attila, giving Walther as a hostage (75–92) | + | ** [[Waltharius75|The Aquitainians under Alphere surrender to Attila, giving Walther as a hostage (75–92)]] |

| − | ** Experience of the hostages at Attila’s court (93–115) | + | ** [[Waltharius93|Experience of the hostages at Attila’s court (93–115)]] |

| − | ** Death of Gibich, flight of Hagen (116–122) | + | ** [[Waltharius116|Death of Gibich, flight of Hagen (116–122)]] |

| − | ** Attila’s queen Ospirin advises her husband to ensure Walther’s loyalty by arranging a marriage (123–141) | + | ** [[Waltharius123|Attila’s queen Ospirin advises her husband to ensure Walther’s loyalty by arranging a marriage (123–141)]] |

| − | ** Walther rejects Attila’s offer of a bride (142–169) | + | ** [[Waltharius142|Walther rejects Attila’s offer of a bride (142–169)]] |

| − | ** Walther leads the army of the Huns to victory in battle (170–214) | + | ** [[Waltharius170|Walther leads the army of the Huns to victory in battle (170–214)]] |

** The Escape (215–418) | ** The Escape (215–418) | ||

| − | *** Walther returns from battle and encounters Hildegund (215–255) | + | *** [[Waltharius215|Walther returns from battle and encounters Hildegund (215–255)]] |

| − | *** Walther reveals to Hildegund his plans for escaping with Attila’s treasure (256–286) | + | *** [[Waltharius256|Walther reveals to Hildegund his plans for escaping with Attila’s treasure (256–286)]] |

| − | *** Walther hosts a luxurious banquet for Attila’s court; eventually all his intoxicated guests fall asleep (287–323) | + | *** [[Waltharius287|Walther hosts a luxurious banquet for Attila’s court; eventually all his intoxicated guests fall asleep (287–323)]] |

| − | *** Flight of Walther and Hildegund from Attila’s court (324–357) | + | *** [[Waltharius324|Flight of Walther and Hildegund from Attila’s court (324–357)]] |

| − | *** The following day, the escape of Walther and Hildegund is discovered by Ospirin (358–379) | + | *** [[Waltharius358|The following day, the escape of Walther and Hildegund is discovered by Ospirin (358–379)]] |

| − | *** Attila is infuriated and vows revenge on Walther, but can find no one willing to dare to pursue him, even for a large reward (380–418) | + | *** [[Waltharius380|Attila is infuriated and vows revenge on Walther, but can find no one willing to dare to pursue him, even for a large reward (380–418)]] |

* The Single Combats (419–1061) | * The Single Combats (419–1061) | ||

** Diplomacy (419–639) | ** Diplomacy (419–639) | ||

| − | *** Flight of Walther and Hildegund to the area of Worms (419–435) | + | *** [[Waltharius419|Flight of Walther and Hildegund to the area of Worms (419–435)]] |

| − | *** Gunther, King of the Franks, learns of Walther’s presence on his territory and, despite Hagen’s warnings, decides to pursue him for his treasure (436–488) | + | *** [[Waltharius436|Gunther, King of the Franks, learns of Walther’s presence on his territory and, despite Hagen’s warnings, decides to pursue him for his treasure (436–488)]] |

| − | *** Walther makes his camp in a mountainous area and goes to sleep (489–512) | + | *** [[Waltharius489|Walther makes his camp in a mountainous area and goes to sleep (489–512)]] |

| − | *** Gunther and his companions approach Walther’s camp; Hagen unsuccessfully tries to dissuade the king from attacking it (513–531) | + | *** [[Waltharius513|Gunther and his companions approach Walther’s camp; Hagen unsuccessfully tries to dissuade the king from attacking it (513–531)]] |

| − | *** Hildegund sees the Franks approaching and wakes Walther, who calms her fears and prepares for battle; he recognizes Hagen from a distance (532–571) | + | *** [[Waltharius532|Hildegund sees the Franks approaching and wakes Walther, who calms her fears and prepares for battle; he recognizes Hagen from a distance (532–571)]] |

| − | *** Hagen persuades Gunther to try diplomacy before using force (571–580) | + | *** [[Waltharius571|Hagen persuades Gunther to try diplomacy before using force (571–580)]] |

| − | *** Camalo is sent as a messenger to Walther, who offers to make Gunther a gift in return for allowing his passage (581–616) | + | *** [[Waltharius581|Camalo is sent as a messenger to Walther, who offers to make Gunther a gift in return for allowing his passage (581–616)]] |

| − | *** Hagen counsels Gunther to accept the offer, but Gunther rejects this advice, calling him a coward. Insulted, Hagen goes off to a nearby hill (617–639) | + | *** [[Waltharius617|Hagen counsels Gunther to accept the offer, but Gunther rejects this advice, calling him a coward. Insulted, Hagen goes off to a nearby hill (617–639)]] |

** Combat (640–1061) | ** Combat (640–1061) | ||

| − | *** 1st single combat: Camalo is sent back to Walther, who slays him (640–685) | + | *** [[Waltharius640|1st single combat: Camalo is sent back to Walther, who slays him (640–685)]] |

| − | *** 2nd single combat: Walther slays Kimo/Scaramund, Camalo’s nephew (686–719) | + | *** [[Waltharius686|2nd single combat: Walther slays Kimo/Scaramund, Camalo’s nephew (686–719)]] |

| − | *** Gunther encourages his men (720–724) | + | *** [[Waltharius720|Gunther encourages his men (720–724)]] |

| − | *** 3rd single combat: Walther slays Werinhard, a descendant of the Trojan Pandarus (725–753) | + | *** [[Waltharius725|3rd single combat: Walther slays Werinhard, a descendant of the Trojan Pandarus (725–753)]] |

| − | *** 4th single combat: Walther slays the Saxon Ekivrid, after an exchange of insults (754–780) | + | *** [[Waltharius754|4th single combat: Walther slays the Saxon Ekivrid, after an exchange of insults (754–780)]] |

| − | *** 5th single combat: Walther slays Hadawart, after an exchange of insults (781–845) | + | *** [[Waltharius781|5th single combat: Walther slays Hadawart, after an exchange of insults (781–845)]] |

| − | *** Hagen sees his nephew Patavrid going off to fight Walther and laments the evil wreaked on mankind by greed (846–877) | + | *** [[Waltharius846|Hagen sees his nephew Patavrid going off to fight Walther and laments the evil wreaked on mankind by greed (846–877)]] |

| − | *** 6th single combat: after trying to dissuade him from fighting, Walther slays Patavrid (878–913) | + | *** [[Waltharius878|6th single combat: after trying to dissuade him from fighting, Walther slays Patavrid (878–913)]] |

| − | *** 7th single combat: Walther slays Gerwitus (914–940) | + | *** [[Waltharius914|7th single combat: Walther slays Gerwitus (914–940)]] |

| − | *** Gunther again encourages his men, giving Walther some time to rest (941–961) | + | *** [[Waltharius941|Gunther again encourages his men, giving Walther some time to rest (941–961)]] |

| − | *** 8th single combat: Walther is shorn of his hair by Randolf, whom he then slays (962–981) | + | *** [[Waltharius962|8th single combat: Walther is shorn of his hair by Randolf, whom he then slays (962–981)]] |

| − | *** Walther is attacked by Eleuthir/Helmnot, assisted by Trogus, Tanastus, and Gunther; he slays all but Gunther (981–1061) | + | *** [[Waltharius981|Walther is attacked by Eleuthir/Helmnot, assisted by Trogus, Tanastus, and Gunther; he slays all but Gunther (981–1061)]] |

* The Final Combat (1062–1452) | * The Final Combat (1062–1452) | ||

| − | ** Gunther tries to persuade Hagen to help him to defeat Waltharius; remembering his wounded honor, Hagen refuses (1062–1088) | + | ** [[Waltharius1062|Gunther tries to persuade Hagen to help him to defeat Waltharius; remembering his wounded honor, Hagen refuses (1062–1088)]] |

| − | ** Hagen changes his mind and agrees to help Gunther, but advises that they must lie low wait until Walther comes down from the mountains into open ground (1089–1129) | + | ** [[Waltharius1089|Hagen changes his mind and agrees to help Gunther, but advises that they must lie low wait until Walther comes down from the mountains into open ground (1089–1129)]] |

| − | ** Walther decides to spend the night in the mountains. He rematches the severed heads with the bodies of his victims, prays for their souls, then sleeps (1130–1187) | + | ** [[Waltharius1130|Walther decides to spend the night in the mountains. He rematches the severed heads with the bodies of his victims, prays for their souls, then sleeps (1130–1187)]] |

| − | ** The following day, Walther and Hildegund set out from the mountains, taking the horses and arms of the defeated warriors (1188–1207) | + | ** [[Waltharius1188|The following day, Walther and Hildegund set out from the mountains, taking the horses and arms of the defeated warriors (1188–1207)]] |

| − | ** Hildegund perceives Gunther and Hagen approaching to attack; the king addresses Walther (1208–1236) | + | ** [[Waltharius1208|Hildegund perceives Gunther and Hagen approaching to attack; the king addresses Walther (1208–1236)]] |

| − | ** Walther ignores Gunther and pleads with Hagen to remember the bond of their childhood friendship; Hagen counters that Walther has already broken their faith by slaying Patavrid (1237–1279) | + | ** [[Waltharius1237|Walther ignores Gunther and pleads with Hagen to remember the bond of their childhood friendship; Hagen counters that Walther has already broken their faith by slaying Patavrid (1237–1279)]] |

| − | ** The fight begins and continues for seven hours; Gunther foolishly tries to retrieve a thrown spear from the ground near Walther and is only saved from death by Hagen’s brave intervention (1280–1345) | + | ** [[Waltharius1280|The fight begins and continues for seven hours; Gunther foolishly tries to retrieve a thrown spear from the ground near Walther and is only saved from death by Hagen’s brave intervention (1280–1345)]] |

| − | ** Walther challenges Hagen; he severs Gunther’s leg, but Hagen again saves the king’s life (1346–1375) | + | ** [[Waltharius1346|Walther challenges Hagen; he severs Gunther’s leg, but Hagen again saves the king’s life (1346–1375)]] |

| − | ** Hagen cuts off Walther’s right hand; Walther gouges out one of Hagen’s eyes and, cutting open his cheek, knocks out four teeth (1376–1395) | + | ** [[Waltharius1376|Hagen cuts off Walther’s right hand; Walther gouges out one of Hagen’s eyes and, cutting open his cheek, knocks out four teeth (1376–1395)]] |

| − | ** Having wounded each other, the warriors end the battle, drink together, and engage in a friendly exchange of humorous taunt (1396–1442) | + | ** [[Waltharius1396|Having wounded each other, the warriors end the battle, drink together, and engage in a friendly exchange of humorous taunt (1396–1442)]] |

| − | ** The warriors return to their respective homes; Walther marries Hildegund and eventually becomes king of the Aquitainians (1443–1452) | + | ** [[Waltharius1443|The warriors return to their respective homes; Walther marries Hildegund and eventually becomes king of the Aquitainians (1443–1452)]] |

| − | * Epilogue (1453–1456)}} | + | * [[Waltharius1453|Epilogue (1453–1456)]]}} |

| | | | ||

|[[Waltharius13|next »]] | |[[Waltharius13|next »]] | ||

Latest revision as of 05:13, 16 December 2009

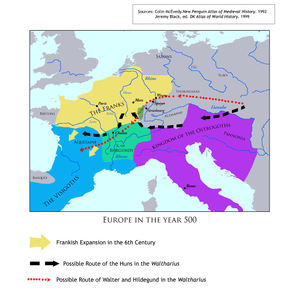

Introduction: the Huns (1–12)

| Tertia pars orbis, fratres, Europa vocatur, | Tertia pars orbis: as opposed to Africa and Asia, a division found as early as Herodotus (2.16). Fratres: suggests that the poem could have been read in a monastic context.

|

Lucan, De Bello Civili 9.411-412.: Tertia pars rerum Libye, si credere famae/ Cuncta velis; at, si ventos caelumque sequaris,/ Pars erit Europae. ‘Libya is the third continent of the world, if one is willing in all things to trust report; but, if you judge by the winds and the sky, you will find it to be part of Europe.’

|

DSSSDS | The opening line of the poem refers to the ancient notion "that the whole earth consists of three divisions, Europe, Asia, and Libya" (Herodotus, 2.16). Not only does it set the general stage of action for the poem (which is Europe) but it is also reminiscent of the opening to Caesar's "De Bello Gallico", "Gallia est omnes divisa in patres tres" (All of Gaul is divided into three parts). The author did not know Greek, however, and most likely was not familiar with Caesar's work. Isidore of Seville's Etymologies XIV.2 was probably more influential, "Divisus est autem trifarie: e quibus una pars Asia, altera Europa, tertia Africa nuncupatur" (It is divided into three parts, one of which is called Asia, the second part Europe, the third Africa). "Fratres": not only does the address "brothers" suggest the possibility of the poem's intended monastic audience, it is also one of the few times in the poem the reader is addressed directly. There is the possibility as well that "fratres" could be taken in the sense of universal brotherhood and would hence include women. Edoardo D'Angelo (1991, p. 166-167) sees here the influence of Lucan, and quotes 9.411-417 from the Bellum Civile: "tertia pars rerum Libye, si credere famae / cuncta uelis; at, si uentos caelumque sequaris, / pars erit Europae. nec enim plus litora Nili / quam Scythicus Tanais primis a Gadibus absunt, / unde Europa fugit Libyen et litora flexu / Oceano fecere locum; sed maior in unam / orbis abit Asiam." JJTY For the wording of the first half line, the likeliest source of inspiration would be Ovid, Metamorphoses 6.372 "agitur pars tertia mundi" (noted recently by Ruben Florio [2002, p. 3]) JZ | ||

| Moribus ac linguis varias et nomine gentes | Aeneid 8.722-723.: gentes,/ quam variae linguis, habitu tam vestis et armis. ‘Peoples as diverse in fashion of dress and arms as in tongues.’ Prudentius, Contra Orationem Symmachi 2.586-587.: discordes linguis populos et dissona cultu/ regna volens sociare Deus. . . ‘God, wishing to bring into partnership peoples of different speech and realms of discordant manners. . .’

|

DSDSDS | ||||

| Distinguens cultu, tum relligione sequestrans. | Sequestrans: “separating,” a meaning that seems to have developed from the concept of the deposit held by a sequester, the third-party arbitrator in a monetary conflict.

|

SSSDDS | "cultu": As distinguished from "religione", it probably can be translated as 'way of life', in the sense of the general style of societal customs, e.g. how they stack their hay, construct and decorate their barns, etc... | |||

| Inter quas gens Pannoniae residere probatur, | Pannonia: Roman province in the north-west Balkans, according to the poet the homeland of the “Huns” (Hunos, line 5), a nomadic tribe that invaded Europe from the east, beginning around 370 A.D.

|

SSDDDS | ||||

| Quam tamen et Hunos plerumque vocare solemus. | 5 | DSSDDS | "Hunos": The Huns first swept into Roman consciousness when, invading from the east, they displaced the Goths, who, as detailed by Ammianus Marcellinus, ended up decimating the Roman army at the Battle of Adrianople, now Edirne in northwest Turkey, in A.D. 378. The province of Pannonia from line 4 was actually ceded to the Huns in the mid-5th century by the Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II after several major military defeats. | |||

| Hic populus fortis virtute vigebat et armis, | DSSDDS | Indeed, the Huns were a nomadic people who flourished not by building cities but by military prowess. Note how the Huns left no literary record nor any real archaeological one beyond military equipment. | ||||

| Non circumpositas solum domitans regiones, | Liber I Macchabeorum 1.1-2.: Et factum est postquam percussit Alexander Philippi Macedo qui primus regnavit in Graecia egressus de terra Cetthim Darium regem Persarum et Medorum constituit proelia multa et omnium obtinuit munitiones et interfecit reges terrae et pertransiit usque ad fines terrae. ‘Now it came to pass, after that Alexander the son of Philip the Macedonian, who first reigned in Greece, coming out of the land of Cethim, had overthrown Darius king of the Persians and Medes: he fought many battles, and took the strong holds of all, and slew the kings of the earth: and he went through even to the ends of the earth.’

|

SDSDDS | ||||

| Litoris oceani sed pertransiverat oras, | Liber I Macchabeorum 1.1-2.: Et factum est postquam percussit Alexander Philippi Macedo qui primus regnavit in Graecia egressus de terra Cetthim Darium regem Persarum et Medorum constituit proelia multa et omnium obtinuit munitiones et interfecit reges terrae et pertransiit usque ad fines terrae. ‘Now it came to pass, after that Alexander the son of Philip the Macedonian, who first reigned in Greece, coming out of the land of Cethim, had overthrown Darius king of the Persians and Medes: he fought many battles, and took the strong holds of all, and slew the kings of the earth: and he went through even to the ends of the earth.’

|

DDSSDS | "oceani": 'Oceanus' in traditional mythology was the son of Uranus and Gaia and the personification of the great river that encircled the known world. Though the extent to which a Carolingian or near-Carolingian monk would have known geography beyond antiquity's understanding of it is unclear, the very same section of Isidore's Etymologies referenced in line 1 explicitly mentions Oceanus as encircling the globe. The Huns were a people of the inland steppes and plains. At the height of its power, the Hunnic Empire stretched from the Caspian and Black Seas to the North Sea and even the Adriatic, but never all the way to the Atlantic Ocean. | |||

| Foedera supplicibus donans sternensque rebelles. | Aeneid 6.851-852.: tu regere imperio populos, Romane, memento/ (hae tibi erunt artes), pacique imponere morem,/ parcere subiectis et debellare superbos. ‘You, Roman, be sure to rule the world (be these your arts), to crown peace with justice, to spare the vanquished and to crush the proud.’

|

DDSSDS | The poet here does not borrow any of the exact language of Aeneid, most notably at 6.852 yet also at 1.257-258, but he does not need to. The allusion to the Virgilian and Roman dictum to "spare the vanquished and crush the proud," an ideal for the imperial Roman leader, is overt. By ascribing this very Roman and ipso facto admirable trait to Attila and the Huns, the poet departs from the view in the ancient Roman's mind of the Huns the scourge of the Roman Empire. This characteristic is factually accurate. Attila and the Huns destroyed many enemy armies, yet they also spared defeated foes in order to exact tribute from them. Indeed, at the very gates of Rome Attila is said to have turned back at the sight of Pope Leo I. | |||

| Ultra millenos fertur dominarier annos. | 10 | Fertur: the subject is populus. Dominarier: archaic form for the passive infinitive (here of a deponent), frequent in poetry of all periods.

|

SSSDDS | This is a case of hyperbole by the author. Perhaps in the medieval mind the name Huns is a reference to an amalgamation of particular antique peripheral invaders, which might explain the reference in line 12 to Attila's wish to renew the "antiquos triumphos." In actuality the Hunnic empire came into existence in the west around 370 when they destroyed a tribe of Alans, and eventually petered out around 469 at the death of Dengizik, the succesor of Attila's son Ellak. Beginning here, but continued throughout the poem, the poet treats the Huns not as barbarians invaders but a strong, proud people with an illustrious history. By putting the Huns on relative par with the Romans (c. line 11) in the way they rule and duration of their "imperium", he strengthens the foundations of his own civilization. Were the Franks and other western European peoples defeated by a mere marauding hoard, there would be no nobility in recalling such story. However, given that the Huns are set up as a broad and powerful civilization, that they were eventually overcome becomes so much more impressive and heroic genesis of the poet's own times. | ||

| Attila rex quodam tulit illud tempore regnum, | Attila: Ruler of the Huns, first with his brother Bleda, from 434 to 455, then alone until 453 A.D. Tulit equiv. togessit

|

DSDSDS | ||||

| Impiger antiquos sibimet renovare triumphos. | Renovare: infinitive following impiger (“eager”); cf. Hor. Carm. 4.14.22.

|

DSDDDS | "antiquos triumphos": c. note on line 10; most likely "antiquos" should be read as 'ancient' or 'ancestral' as opposed to 'old', which would lend itself to the grandeur with which the poet tries to infuse the Huns. Attila is not attempting to rekindle the fame of his own younger days, but the younger days of his people. |